Drug Safety Risk Calculator

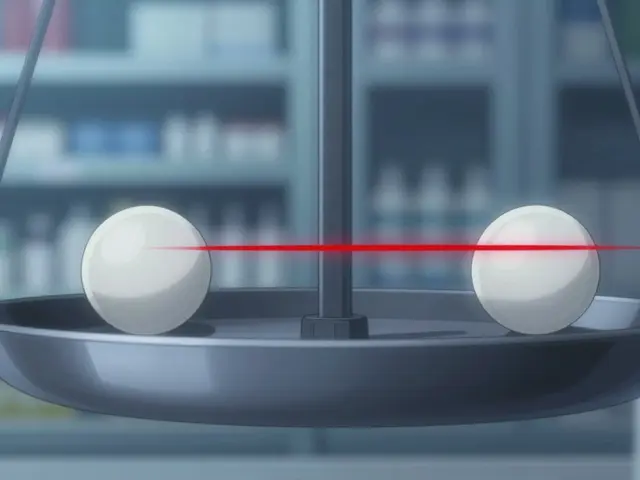

This tool demonstrates how the FDA Sentinel Initiative calculates true drug safety risk rates by comparing patients who took a drug with those who didn't. Enter your hypothetical data to see how Sentinel's approach provides more accurate risk assessment than voluntary reporting systems.

Risk Assessment

Risk rate:

This means

Why Sentinel Matters

Traditional reporting systems like FAERS only collect voluntary reports. If 100 people reported a side effect but 10 million took the drug, you'd never know it's 1 in 100,000. Sentinel calculates this exact risk rate using real-world data from millions of patients.

The FDA Sentinel Initiative isn’t just another government database. It’s the largest distributed health data network in the world built to catch dangerous side effects from medications before they kill more people. Unlike old-school systems that wait for doctors or patients to report problems, Sentinel actively hunts for hidden risks using real-world data from millions of patients. It doesn’t collect data in one place-it asks trusted partners to run queries on their own systems and send back only the results. This keeps patient privacy intact while giving regulators a powerful new lens to see what’s really happening after a drug hits the market.

How Sentinel Changed the Game

Before Sentinel, the FDA relied mostly on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), where doctors, pharmacists, or patients voluntarily report side effects. The problem? Less than 1% of serious reactions get reported. Many people don’t connect a new symptom to a drug they took months ago. Others don’t know where to report. And even when reports come in, there’s no way to know how many people were taking the drug in the first place-so you can’t tell if a side effect is rare or common. Sentinel fixed that. It started in 2008, after Congress gave the FDA a clear order: monitor drug safety using real-world data. The first test phase, called Mini-Sentinel, ran from 2009 to 2015. It proved that health insurers and hospital systems could safely share data without giving up control of their records. By 2016, the full system was live. Today, it pulls data from over 200 organizations-including big insurers like UnitedHealthcare, hospital networks like Kaiser Permanente, and government programs like Medicare. That’s more than 250 million patient records, updated quarterly.The Distributed Network Model

Here’s the clever part: no one sends raw data to the FDA. Instead, when a red flag pops up-say, a spike in heart attacks after a new diabetes drug launches-the FDA writes a query. That query gets sent out to every data partner. Each one runs it on their own servers using the same software. They don’t send names, addresses, or Social Security numbers. They just return a number: “Among 12 million people who took Drug X, 47 had heart attacks in the first 30 days. Among 10 million who took Drug Y, 18 did.” This model protects privacy and avoids legal headaches. It also means the system can grow fast. New partners join without having to rebuild their entire data infrastructure. And because data stays local, it’s easier to comply with state and federal rules. The downside? Making sure every partner codes conditions and drugs the same way. A heart attack in one system might be labeled as “MI,” in another as “myocardial infarction.” The FDA’s Innovation Center spends a lot of time standardizing these terms.From Claims Data to Clinical Notes

Early on, Sentinel mostly used insurance claims data-things like diagnosis codes, prescriptions filled, and hospital visits. It’s reliable, but limited. You won’t find details like “patient had dizziness after taking the pill” or “family noticed confusion.” That’s where electronic health records (EHRs) come in. Since 2021, Sentinel has been integrating structured and unstructured EHR data. That means pulling out notes from doctor visits, lab results, and even free-text descriptions like “patient reported feeling like her heart was racing.” Natural language processing-a form of AI-helps dig through those notes to find patterns. One recent project used AI to scan 500,000 clinical notes to detect early signs of liver damage from a new weight-loss drug. The system flagged 12 cases that had never been reported to FAERS. The Innovation Center now focuses on four big areas: better data tools, smarter ways to extract meaning from messy data, stronger methods to prove cause-and-effect, and faster detection of signals. They’re testing machine learning models that can predict which drugs might cause rare side effects based on how similar drugs behaved in the past.

Real Impact: When Sentinel Stopped a Dangerous Drug

In 2019, a new osteoporosis drug showed up in FAERS with a few reports of unusual strokes. But the numbers were too low to act on. Sentinel stepped in. They ran a query across 150 million patient records. The result? People taking the drug had a 3.5 times higher risk of stroke within the first 90 days compared to those on older treatments. The FDA paused sales, asked the manufacturer to run a new trial, and eventually added a strong warning to the label. Without Sentinel, that signal might have been ignored for years. Another example: in 2020, Sentinel detected a spike in Guillain-Barré syndrome after a new flu vaccine. The signal was small-just 12 extra cases per million doses-but the system caught it within weeks. That’s faster than any traditional study could have. The FDA updated the vaccine’s safety info, and manufacturers improved their manufacturing process.Who Uses Sentinel and Why

It’s not just the FDA. Pharmaceutical companies use it to monitor their own drugs after launch. Academic researchers get access to anonymized data for studies. International regulators like the European Medicines Agency and Health Canada have started building similar systems based on Sentinel’s model. Even Medicare uses it to track drug safety in older adults, a group often left out of clinical trials. The system’s three main centers handle different roles: the Operations Center runs queries, the Innovation Center builds new tools, and the Community Building Center trains users and brings in new partners. There’s even a portal where researchers can request access to test their own ideas-something that didn’t exist before.

Limitations and Challenges

Sentinel isn’t perfect. It still misses rare side effects that happen in fewer than 1 in 10,000 people. It can’t track what patients do outside the healthcare system-like taking herbal supplements or skipping doses. And while AI helps, it still struggles with poorly written notes or missing information. Some researchers say the learning curve is steep. Writing a good query requires training in epidemiology, statistics, and health informatics. Not every academic lab has those skills. The FDA offers free training, but it takes time. Also, because data updates quarterly, Sentinel isn’t truly real-time. It’s fast compared to old methods, but not instant. For fast-moving threats like a contaminated batch of medicine, other tools are still needed.The Future: Sentinel 3.0 and Beyond

In 2023, the FDA announced a major funding boost-$304 million-for what’s being called Sentinel 3.0. This version will focus on deeper integration of EHRs, better AI tools to interpret clinical notes, and tighter links with global health systems. The goal? To build a worldwide network where drug safety signals can be detected faster, no matter where they appear. Dr. Robert Califf, former FDA commissioner, called Sentinel “an indispensable tool.” And it’s becoming more than just a safety net. It’s becoming a learning system-where every prescription, every lab result, every hospital visit helps improve the next generation of drugs.Why This Matters to You

If you or someone you know takes prescription medication, Sentinel is working behind the scenes to make sure it’s safe. It’s the reason new drugs get better warning labels. It’s why rare side effects get caught before they spread. It’s why you can trust that when a drug gets approved, regulators aren’t just guessing-they’re using real data from millions of real people. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t make headlines. But every time a dangerous drug gets pulled or a warning gets added, Sentinel played a part.How is Sentinel different from the FDA’s adverse event reporting system (FAERS)?

FAERS relies on voluntary reports from doctors, patients, or manufacturers. It’s full of gaps-many events go unreported, and there’s no way to know how many people took the drug. Sentinel uses actual health records from millions of patients, so it can calculate true risk rates. For example, if 100 people out of 10 million taking a drug have a side effect, Sentinel can tell you that’s 1 in 100,000. FAERS can’t do that.

Does Sentinel collect personal health information?

No. Sentinel never collects or stores personal data like names, addresses, or medical record numbers. Data stays with the original provider-hospitals, insurers, or clinics. The FDA only gets aggregated numbers, like “12 cases of liver injury among 5 million users.” All identifying details are removed before any analysis.

Can researchers outside the FDA use Sentinel?

Yes. The Sentinel Innovation Center runs demonstration projects that allow academic researchers, public health agencies, and even pharmaceutical companies to propose and run safety studies using the network. You need to apply, get approved, and follow strict protocols, but access is open to qualified users.

How long does it take for Sentinel to detect a safety issue?

It varies. Simple queries can return results in 2-4 weeks. More complex studies, especially those using EHR data or needing custom analysis, can take 3-6 months. That’s still much faster than traditional observational studies, which often take years to design and complete.

Is Sentinel used only in the U.S.?

The system is U.S.-based, but its model is being copied worldwide. The European Union, Canada, Japan, and Australia are building similar distributed networks based on Sentinel’s architecture. The goal is to create a global safety network where signals can be shared across borders-especially for drugs used internationally.

9 Comments

phara don

February 4, 2026This is actually wild. I had no idea the FDA was running something this advanced. The way they keep data local but still get aggregate stats? Genius. And the fact that they caught that stroke risk with the osteoporosis drug? That’s life-saving tech right there.

Also, AI scanning 500k clinical notes for liver damage? That’s not science fiction anymore. We’re living in the future.

Hannah Gliane

February 5, 2026Oh wow 🙄 another government program that somehow didn’t waste billions. Who knew? Maybe if we stopped funding fighter jets and started funding this, we wouldn’t need to bury half our grandparents from bad prescriptions. 🤦♀️💊

Murarikar Satishwar

February 6, 2026The distributed architecture of Sentinel is a masterclass in privacy-preserving data analytics. Unlike centralized systems that invite breaches and regulatory conflict, this model respects data sovereignty while enabling population-level insights. The standardization of terminologies across heterogeneous EHRs remains a formidable challenge, yet the Innovation Center’s work on ontology alignment is commendable. This is public health infrastructure at its finest.

Dan Pearson

February 7, 2026So let me get this straight - America built a system that actually works better than the rest of the world’s? Of course we did. 🇺🇸

Meanwhile, Europe’s still arguing over whether to use ‘MI’ or ‘myocardial infarction’ like it’s a damn debate club. We don’t just lead the world in tech - we lead in saving lives without asking permission. Send this to the WHO. Let them copy it. Again.

Bob Hynes

February 8, 2026Man I love this. Canada’s kinda trying to build something similar but we’re still stuck using fax machines for some prescriptions 😅

But seriously - this is the kind of thing that makes me proud to be from North America. We’re not just reacting to disasters anymore, we’re predicting them. Also, the fact that they’re using AI on doctor’s messy handwriting? That’s like giving a robot a PhD in medical slang.

Akhona Myeki

February 10, 2026I am genuinely astonished that such a sophisticated system exists in the United States of America. One would assume that bureaucratic inefficiency would prevent such innovation. Yet here we are - a functioning, scalable, privacy-compliant surveillance network for pharmaceutical safety. The implications for global health governance are profound.

Brett MacDonald

February 12, 2026it’s funny how we think tech is gonna save us but we still let pharma companies write the rules. sentinel’s cool and all but who’s really controlling the queries? who decides what’s a ‘red flag’? maybe it’s just another way to make drugs look safer while the real problems get buried under ‘statistical noise’.

Sandeep Kumar

February 13, 2026Sentinel is just fancy stats with a government stamp. Real problem? Doctors don’t even know what’s in their own EHRs. And the FDA? They approve drugs based on 6 month trials then act shocked when people die a year later. This is damage control not prevention

Gary Mitts

February 15, 2026So basically they turned every hospital and insurer into a spy for drug safety. Cool. 😎