HIV NRTI Drugs: What They Are and Why They Matter

When working with HIV NRTI drugs, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors that block the HIV enzyme responsible for copying viral RNA. Also known as NRTIs, they are a cornerstone of modern HIV treatment. Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors form a broader class that includes both nucleoside and non‑nucleoside types, while Tenofovir is one of the most widely prescribed agents in this group. Understanding how these pieces fit together helps anyone from a new patient to a seasoned clinician navigate HIV therapy.

At the molecular level, HIV NRTI drugs work by mimicking the natural building blocks of DNA. Once inside a infected cell they get incorporated into the growing viral DNA chain, causing premature termination. In short, they inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that normally converts viral RNA into DNA. This inhibition is a classic example of a subject‑predicate‑object relationship: HIV NRTI drugs target reverse transcriptase to stop viral replication. Because the virus can’t complete its genome, the infection’s spread slows dramatically, giving the immune system a chance to recover.

How NRTIs Fit Into Antiretroviral Therapy

HIV treatment rarely relies on a single drug. Instead, clinicians combine NRTIs with other classes like protease inhibitors and non‑nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) to create a potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen. The triple‑drug approach reduces the chance that the virus will develop resistance. In practice, an ART plan might pair two NRTIs—say, Emtricitabine and Zidovudine—with an NNRTI like efavirenz. This combination leverages different mechanisms to achieve stronger viral suppression, embodying the semantic triple: antiretroviral therapy includes NRTIs, NNRTIs, and protease inhibitors.

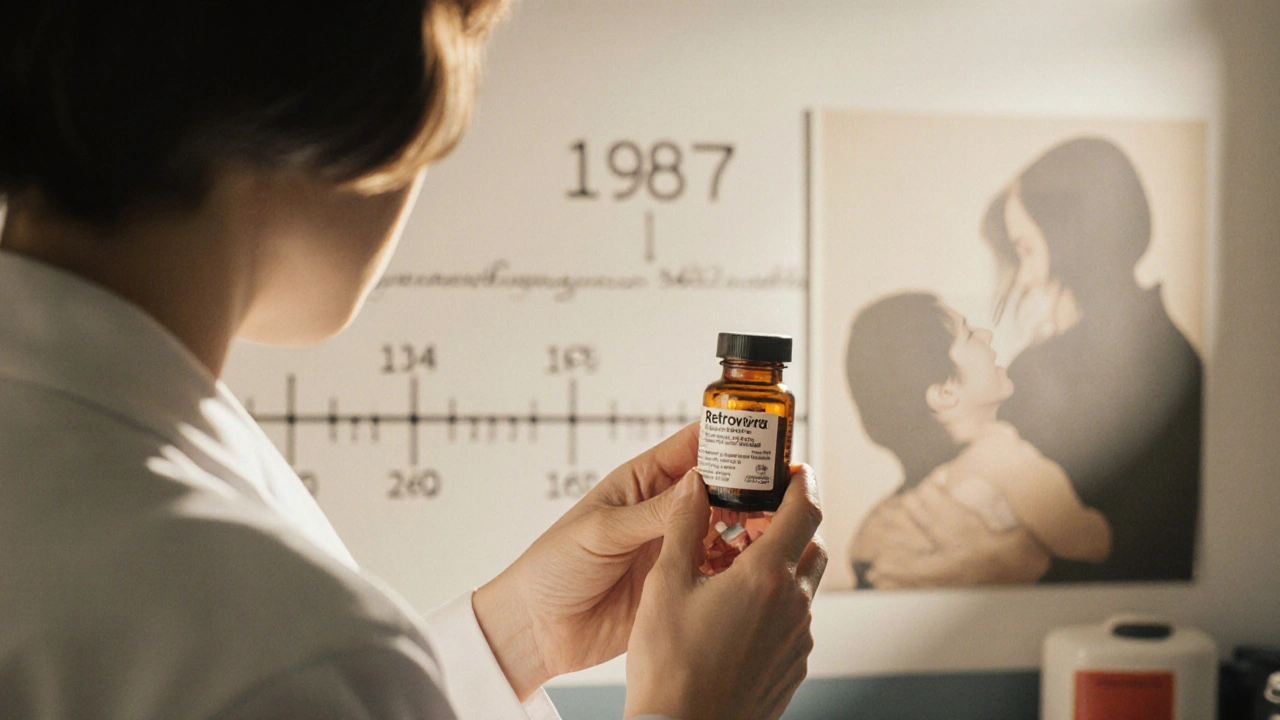

Not all NRTIs are created equal. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and its newer sibling tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) offer high potency with a better safety profile for kidneys and bone density. Emtricitabine (FTC) pairs well with tenofovir because both have long intracellular half‑lives, allowing once‑daily dosing. Zidovudine (AZT), one of the earliest NRTIs, is still useful in certain scenarios, especially for preventing mother‑to‑child transmission. Each drug carries specific attributes—such as dosage frequency, side‑effect spectrum, and drug‑interaction potential—that influence how clinicians build an individualized regimen.

Resistance testing and routine monitoring are essential when using NRTIs. Mutations in the reverse transcriptase gene can reduce a drug’s effectiveness, prompting a switch to a different NRTI or adding a boosted protease inhibitor. Patients also need to watch for common side effects: tenofovir can affect kidney function, emtricitabine may cause mild rash, and zidovudine often leads to anemia. By staying on top of lab results and symptom checks, clinicians can adjust therapy before the virus gains a foothold. This proactive approach illustrates another semantic link: proper monitoring prevents resistance, which maintains treatment success.

Below you’ll find a curated selection of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics—drug‑specific guides, safety tips, cost‑saving strategies, and more. Whether you’re looking for a quick refresher on tenofovir dosing or need detailed instructions on safely purchasing generic HIV meds online, the posts ahead cover the full spectrum of practical information you’ll need to manage HIV NRTI therapy effectively.

Retrovir (Zidovudine) vs Alternative NRTIs: A Comprehensive Comparison

A detailed comparison of Retrovir (Zidovudine) with modern NRTI alternatives, covering efficacy, safety, cost, pregnancy use, and when to choose each drug.

Continue Reading