When you’re on Medicaid, getting your prescriptions filled shouldn’t be a maze. But if you’ve ever tried to fill a generic medication across different states, you know it’s anything but simple. One state might automatically swap a brand-name drug for its generic version without asking. Another might require your doctor to jump through five hoops just to approve the same pill. And in some places, you’ll pay $1 for that generic. In others, it’s $8. Why? Because Medicaid isn’t a single program. It’s 51 different programs - one for each state and Washington, D.C. - each with its own rules, formularies, and hidden barriers.

How Medicaid Covers Generics: The Federal Floor, State Ceiling

Federal law doesn’t force states to cover prescription drugs. But every single state does. Why? Because without drug coverage, people skip doses, end up in the ER, and costs go up. So since 2025, all 50 states and D.C. cover outpatient prescriptions for Medicaid enrollees. But that’s where the uniformity ends.

The federal government sets the baseline: all drugs from manufacturers enrolled in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program must be covered - except a few banned categories like weight-loss drugs, fertility treatments, and erectile dysfunction meds. Beyond that, states have near-total control. They decide which generics go on their formularies, who can substitute them, how much you pay, and whether your doctor needs to beg for approval before you get your medicine.

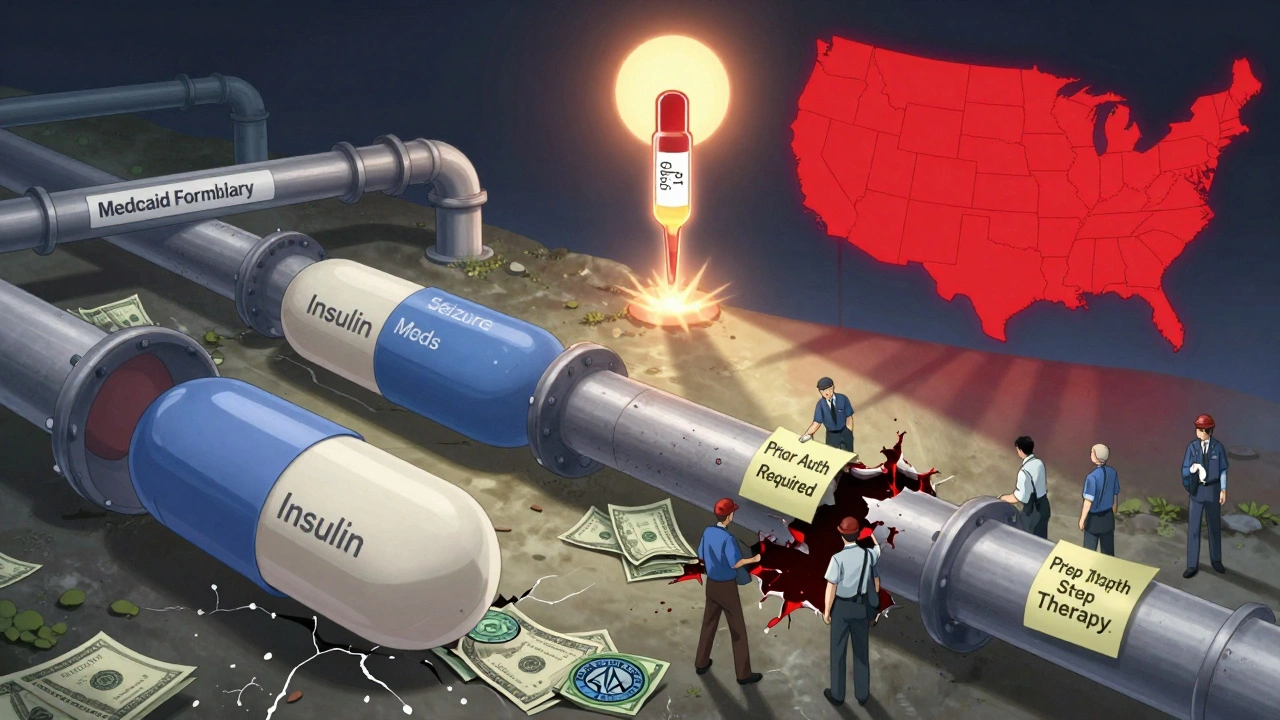

Here’s the real kicker: 84.7% of all Medicaid drug claims are for generics. That’s over 1.2 billion prescriptions a year. But even though generics are cheaper, states still spend $38.7 billion on them annually. Why? Because prices for some critical generics - like insulin, seizure meds, or antibiotics - have skyrocketed in recent years. So states aren’t just managing access. They’re fighting to keep these drugs affordable.

Automatic Generic Substitution: Not a Right, But a Rule in Most States

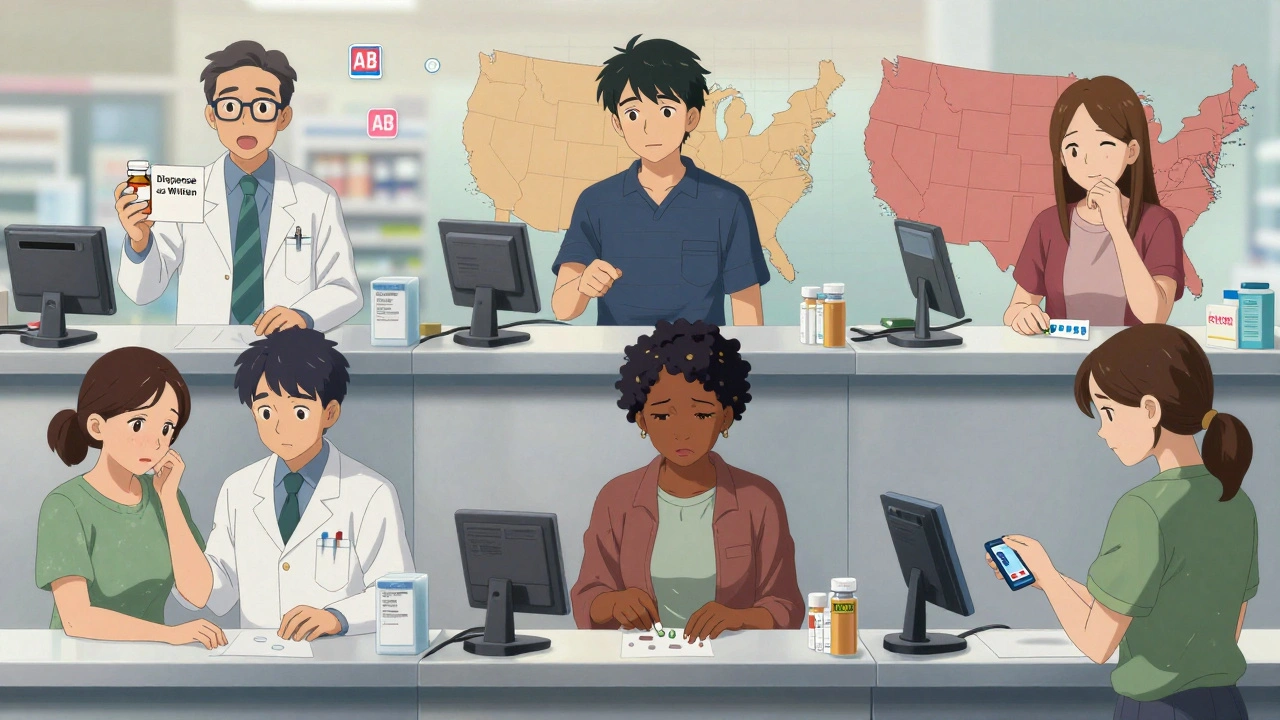

Imagine your doctor writes a script for Lipitor. Your pharmacist hands you atorvastatin - the generic - without asking. That’s automatic substitution. It’s legal in 41 states as of 2025. But it’s not automatic everywhere.

In Colorado, state law says pharmacists must substitute a generic unless:

- The prescriber writes “dispense as written” on the script

- The brand-name drug is actually cheaper than the generic (yes, that happens)

- You’ve been stable on the brand for months and switching could hurt your health

But in California, the rules are looser. Pharmacists can substitute generics unless the doctor says no - but they don’t have to. It’s optional. In Texas, substitution is allowed, but only if the generic is on the state’s Preferred Drug List. And in some states, like Mississippi, pharmacists aren’t even required to tell you they switched your pill.

Forty-six states now use the FDA’s therapeutic equivalence ratings (the “AB” codes) to decide what can be swapped. But that doesn’t mean the rules are the same. Some states let pharmacists make the call. Others require prior approval from the prescriber. And in 28 states, the pharmacist must document why they made the switch. In 12, they don’t have to say a word.

Formularies and Tiers: Your Medicine’s Social Class

Every state has a formulary - a list of covered drugs. But they’re not just lists. They’re tiered systems that rank medicines by cost and preference.

Most states use a three-tier system:

- Tier 1: Preferred generics - cheapest, no prior auth, lowest copay

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics or brand-name drugs - higher copay, may need approval

- Tier 3: Specialty drugs - high cost, strict rules, often require step therapy

CVS Caremark, which runs pharmacy benefits for 17 states, uses this structure. But what’s “preferred” in New York might be “non-preferred” in Florida. Why? Because each state negotiates separately with drugmakers and PBMs (Pharmacy Benefit Managers). States like Michigan and Washington have started using “value-based purchasing” - paying less for drugs that keep people out of the hospital. Only 9 states have tried this so far, but it’s growing.

Some states go further. Colorado’s Preferred Drug List (PDL) includes clinical rules you won’t find anywhere else. To get approved for a certain GI drug, you might need to try and fail three other preferred NSAIDs and three proton pump inhibitors first. That’s step therapy - and it’s in 32 states.

Prior Authorization: The Hidden Bureaucracy

Even if your drug is on the formulary, you might still need prior authorization. That’s when your doctor calls or submits paperwork to prove you need the drug. It’s common for opioids, mental health meds, and non-preferred generics.

In Colorado, most preferred generics don’t need prior auth. But if you’re on a non-preferred generic - say, a generic version of a drug that’s been on the market for 15 years - you’re stuck waiting. Some states approve these in 24 hours. Others take up to 72.

And it’s not just about time. It’s about stress. A 2025 American Medical Association report found that primary care doctors spend an average of 15.3 minutes per patient just handling prior auth for generic meds. That’s over $8,200 a year in lost time per doctor. For patients, it means missed doses, delayed refills, or giving up entirely.

One study from the University of Pennsylvania found that when Medicaid patients got denied a generic switch, their hospital admissions jumped by 12.7%. That’s not just a paperwork problem. It’s a health crisis.

Copays: Paying More for the Same Pill

You’d think a generic pill costs the same everywhere. But your out-of-pocket cost? That’s all up to your state.

Federal rules let states charge up to $8 for non-preferred generics if your income is below 150% of the poverty line. But most states charge far less. In Ohio, it’s $1. In Oregon, it’s $2. In Texas, it’s $4. In some states, like Alabama, you pay nothing at all for Tier 1 generics.

But here’s the catch: those low copays often come with strings. States with $1 copays usually have tighter formularies. You get cheap meds - but fewer choices. States with higher copays often have wider formularies. You can get more drugs - but you pay more.

And if you’re dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid? You can change your drug plan once a month. That means your copay could change every 30 days. No other insurance system works like that.

Who’s Running the Show? PBMs and the Hidden Players

Behind every state’s Medicaid pharmacy program is a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx manage benefits for 37 states as of 2025. These companies negotiate drug prices, build formularies, and decide which drugs get approved.

But they’re not public agencies. They’re private companies - and they’re paid based on how much they save. That creates a conflict. They want to cut costs, but they also get paid a percentage of the drug price. So if they push you toward a cheaper generic, they might make less money.

Some states are catching on. Michigan started paying PBMs based on patient outcomes - not just savings. That led to an 11.2% drop in costs for diabetes meds without dropping adherence. But most states still pay PBMs the old way. And that’s why your formulary feels like a mystery.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The biggest shift coming? Anti-obesity drugs. In December 2024, CMS proposed a rule that would require all Medicaid programs to cover GLP-1 drugs like Wegovy and Ozempic - even though they’re brand-name and expensive. If it passes, it’ll be the first major expansion of mandatory drug coverage since the Affordable Care Act. That could affect 4.7 million people.

But there’s a dark cloud. A bill in Congress would remove inflation-based rebates from most generic drugs. Right now, drugmakers pay back rebates if prices rise faster than inflation. If that changes, states could lose $1.2 billion a year in federal rebates. That means higher copays, tighter formularies, or both.

Meanwhile, supply chain issues are making some generics scarce. In 2024, 17 Medicaid-covered generics were on the FDA’s shortage list - including antibiotics, blood pressure meds, and seizure drugs. States are scrambling to find alternatives. And in some places, that means switching patients mid-treatment - again.

What You Can Do: Navigating Your State’s System

If you’re on Medicaid and rely on generics, here’s what to do:

- Get your state’s current Preferred Drug List. Most are online. Search “[Your State] Medicaid PDL 2025”.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this generic on the preferred list?” If not, ask if there’s a cheaper alternative.

- If you’re denied a drug, ask for a medical exception. You have the right to appeal.

- Keep a list of all your meds - including the generic names. That helps if your pharmacy switches them without telling you.

- Call your state’s Medicaid office. Ask about copay limits and prior auth timelines. They’re required to tell you.

And if you’re a provider? Know your state’s substitution laws. Know your formulary. And don’t assume your patient’s experience in one state matches another. Medicaid isn’t one program. It’s 51 different systems - and they’re all changing.

Do all states cover generic drugs under Medicaid?

Yes. All 50 states and Washington, D.C., cover outpatient prescription drugs for Medicaid enrollees as of 2025. While federal law doesn’t require it, every state has chosen to include pharmacy benefits because it reduces long-term healthcare costs and improves health outcomes.

Can a pharmacist automatically switch my brand-name drug to a generic?

In 41 states, pharmacists are legally allowed - and sometimes required - to substitute a generic for a brand-name drug if it’s rated as therapeutically equivalent by the FDA. But the rules vary: some states require the prescriber to allow substitution, others let the pharmacist decide, and a few require notification to the doctor. Always check your state’s specific laws.

Why is my generic drug not covered even though it’s on the formulary?

Even if a drug is on your state’s formulary, it may still need prior authorization. Some states require prior auth for non-preferred generics, especially if they’re used for conditions like pain, mental health, or chronic illness. Others limit quantities or require step therapy - meaning you must try cheaper alternatives first. Check your state’s Preferred Drug List for restrictions.

How much can I be charged for a generic drug under Medicaid?

Federal rules allow states to charge up to $8 for non-preferred generics if your income is below 150% of the federal poverty level. Most states charge less - often $1 to $4. Some charge nothing for preferred generics. Copays vary by state, tier level, and whether you’re dually eligible for Medicare. Always ask your pharmacy for your exact copay before filling your prescription.

What happens if my state stops covering a generic drug I rely on?

If your state removes a drug from its formulary, you have the right to request a medical exception. Your doctor can submit documentation proving the drug is medically necessary and that alternatives won’t work. You can also appeal the decision. Many states have a 30-day window for appeals. Keep records of all prescriptions, denials, and communications - they’re critical for your case.

Are there any new Medicaid generic coverage rules coming in 2025?

Yes. CMS proposed a rule in late 2024 requiring all Medicaid programs to cover anti-obesity drugs like Wegovy and Ozempic. If finalized, this will be the first major expansion of mandatory drug coverage since the ACA. At the same time, Congress is considering legislation that would remove inflation-based rebates from most generic drugs - which could cost states $1.2 billion annually and lead to tighter coverage rules. Stay updated through your state’s Medicaid website.

8 Comments

Donna Hammond

December 12, 2025I’ve been on Medicaid for six years, and I can tell you-this post nails it. In Texas, I once waited three weeks for a generic blood pressure med because it wasn’t on the preferred list. My doctor had to submit five forms. I missed doses. My BP spiked. No one at the state office even apologized. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s a health risk.

Richard Ayres

December 13, 2025While the disparities in Medicaid coverage are deeply concerning, it’s worth acknowledging that states are operating under vastly different fiscal constraints and political environments. The fact that 84.7% of claims are for generics speaks to a system that, despite its flaws, prioritizes cost-effective care. Reform is needed, but it must be nuanced and grounded in data, not outrage.

Sheldon Bird

December 15, 2025Yo, this is wild but also so real 😅 I had to switch from one generic antidepressant to another because my state dropped the first one. My therapist said it was "therapeutically equivalent"-but my brain didn’t agree. Took me 3 months to stabilize. Just saying: generics aren’t all created equal. We need better monitoring, not just cheaper pills. 🙏

Karen Mccullouch

December 17, 2025Of course the government lets private PBMs run the show. That’s why your insulin costs $400 even when it’s "generic." Big Pharma and CVS are laughing all the way to the bank while we’re skipping doses. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a scam. And don’t tell me "it’s state-run"-they’re all in bed with the same corporations. Wake up, people!

Ronan Lansbury

December 18, 2025Let’s be honest-this entire Medicaid structure is a distraction. The real issue is that the U.S. spends more per capita on healthcare than any nation on Earth, yet still can’t guarantee consistent drug access. The formularies? The PBMs? The copays? All theater. The truth is, if you’re poor, you’re being systematically denied care under the guise of fiscal responsibility. It’s not broken. It was designed this way.

Jennifer Taylor

December 20, 2025OMG I JUST GOT DENIED FOR MY GENERIC ZOLOFT AGAIN AND MY THERAPIST SAID SHE’S GOING TO QUIT BECAUSE SHE’S SPENDING 4 HOURS A DAY ON PRIOR AUTHS 😭 I’M ON MEDICAID IN FLORIDA AND THEY MADE ME TRY 7 OTHER DRUGS FIRST-7!!! I’M NOT A LAB RAT. MY DOCTOR EVEN CALLED THEM AND THEY SAID "THEY’RE ALL EQUIVALENT" BUT THEY’RE NOT. I’M CRYING RIGHT NOW. WHO DO I CALL???

Shelby Ume

December 22, 2025Hi everyone-I’m a nurse in Ohio, and I want to say thank you for this thread. I’ve been helping patients navigate these systems for over a decade. One thing I always tell them: ask for the formulary. Ask for the appeal form. Ask if there’s a tier exception. You have rights. And if your pharmacist doesn’t explain your copay, ask again. You’re not being difficult-you’re being smart. Keep pushing. You’re not alone.

Jade Hovet

December 22, 2025ok so i just found out my state changed my generic from amlodipine to something i’ve never heard of and now my ankles are swollen?? 🤯 i called the pharmacy and they said "it’s the same thing!" but it’s not!! i’m so mad. also i think they switched my meds again last week and didn’t tell me 😭 anyone else have this happen?? p.s. i’m in kansas and they don’t even send you a notice!!