When Hurricane Helene hit North Carolina in September 2024, it didn’t just knock out power and flood homes-it triggered a nationwide crisis in hospitals. Within 72 hours, intravenous (IV) fluids, the lifeline for patients receiving chemotherapy, surgery, or antibiotics, began disappearing from shelves. Hospitals were forced to delay elective procedures, ration fluids, and scramble for alternatives. This wasn’t an accident. It was the result of a supply chain built on fragile, concentrated hubs that climate change is now breaking apart.

Why One Storm Can Break the Whole System

The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain doesn’t look like a network. It looks like a spiderweb with a few thick threads holding everything together. Puerto Rico used to produce 10% of all FDA-approved drugs and 40% of sterile injectables. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, it took 18 months to restore insulin supplies because the island’s power grid was destroyed and took 11 months to fix. Today, the same problem is happening in North Carolina. Baxter International’s plant in North Cove makes 60% of the country’s IV fluids. When Helene flooded the facility, the entire U.S. supply chain buckled.It’s not just hurricanes. Tornadoes, floods, and wildfires are hitting manufacturing sites too. In 2023, a tornado damaged Pfizer’s facility in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, cutting off 27 specific medicines. In 2022, flooding in Michigan hit Abbott’s infant formula plant-already in crisis-extending shortages by eight weeks. These aren’t isolated events. They’re symptoms of a system designed for efficiency, not resilience.

Where the Drugs Are Made-and Why That’s a Problem

Nearly two-thirds of U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities are located in counties hit by at least one weather disaster between 2018 and 2023. The problem isn’t just that these places get storms. It’s that they’re the only places making certain drugs.Take sterile injectables. About 78% of these life-saving medications have only one or two manufacturers in the entire country. If that one plant goes down, there’s no backup. Insulin, saline, antibiotics, and chemotherapy drugs are all made in just a handful of locations. Puerto Rico still hosts 55 FDA-approved drug plants. Spruce Pine, North Carolina, supplies 90% of the quartz used in medical device chips. One town. One raw material. One disaster away from a nationwide shortage.

This concentration isn’t accidental. It’s cheaper to build large factories in places with low labor costs and tax incentives. But it’s dangerous. Unlike cars or phones, you can’t quickly switch suppliers for a drug that’s been approved by the FDA. Getting a new facility up and running takes 6 to 12 months. Specialized equipment? That can take 2 to 3 years. When disaster strikes, there’s no fast-forward button.

Why Hurricanes Are the Worst Threat

Not all natural disasters hit pharmaceutical supply chains the same way. Hurricanes are the most destructive. They knock out power for weeks, flood production lines, and damage transportation routes. Between 2017 and 2024, hurricanes caused 47% of all climate-related drug shortages-more than wildfires, floods, and heat combined.Hurricane Maria didn’t just break Puerto Rico’s grid-it broke trust in the system. Fourteen critical drugs went into shortage. Saline solution lasted 14 months. Hospitals had to prioritize who got fluids. Cancer patients waited. Newborns were put on lower doses. Elderly patients skipped treatments. The FDA eventually allowed imports from Europe, but it took 28 days to approve them. By then, damage was done.

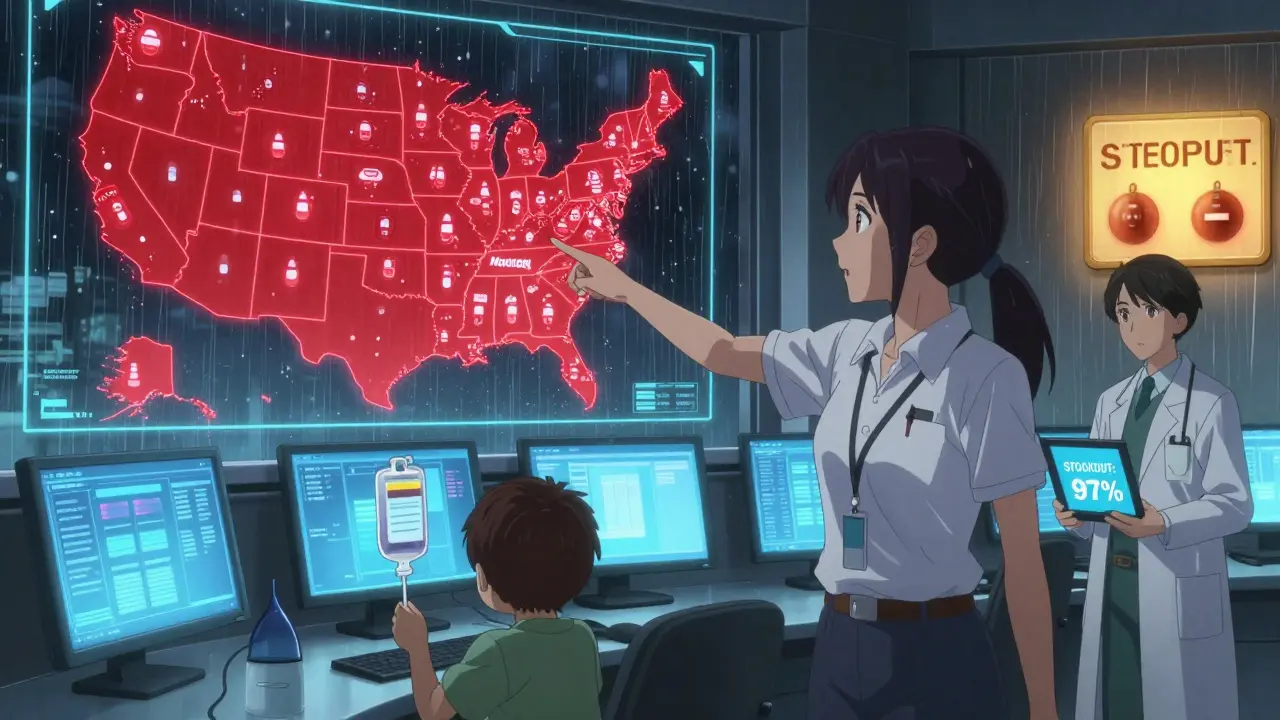

Hurricane Helene in 2024 repeated the pattern. The IV fluid shortage hit within days. Hospitals didn’t have time to prepare. The Strategic National Stockpile had a pilot program for emergency injectables, and it helped reduce the shortage duration by 40% compared to Maria. But that’s still not enough. We’re reacting after the fact-never before.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

There are signs that the system is starting to wake up. The FDA now officially lists natural disasters as a top cause of drug shortages. In October 2024, they proposed a new rule: manufacturers of critical drugs must keep a 90-day emergency inventory and submit climate risk plans. That’s a start. But it’s still voluntary for most drugs.Some companies are using AI to predict disasters. Sensos.io, a supply chain analytics firm, flagged Hurricane Helene’s threat to IV fluids 14 days in advance. A few hospitals used that warning to stockpile extra fluids. But most didn’t. Why? Because mapping your entire supply chain-from raw materials to final packaging-takes 6 to 9 months. Only 31% of top pharmaceutical companies have implemented real mitigation strategies. And only 68% even do climate vulnerability assessments.

Big hospitals with 500+ beds are 3.2 times more likely to have supply chain maps than small clinics. That means rural hospitals, community health centers, and low-income areas will suffer the most when the next storm hits. The system isn’t just broken-it’s unequal.

The Cost of Inaction

The financial cost of fixing this is real. Experts estimate it would take $12 to $15 billion to build a more resilient supply chain-spreading production across three climate-resilient zones, investing in backup power, diversifying suppliers. That could cut shortage frequency by 70%. But the cost of doing nothing is higher.By 2030, climate models predict a 25-30% increase in Category 4 and 5 hurricanes. That means more storms hitting the same high-risk zones. The American Society of Clinical Oncology warns that by 2027, cancer patients will face treatment delays during 8 to 10 major climate disasters every year. That’s not speculation. It’s a projection based on today’s infrastructure.

Some argue that moving manufacturing back to the U.S. would raise drug prices by 15-25%. But what’s the price of a patient missing chemotherapy because the IV bag wasn’t delivered? What’s the cost of a newborn in the NICU getting diluted fluids because the full-strength ones ran out?

What Needs to Happen Next

There are three urgent steps that must happen:- Require emergency stockpiles for critical drugs. Saline, insulin, antibiotics, and cancer drugs must have federally mandated 90-day reserves stored in geographically separate locations.

- Force manufacturers to map their entire supply chain. No more hidden dependencies. Every Tier 1, 2, and 3 supplier must be documented and assessed for climate risk.

- Create fast-track approval for alternative suppliers during disasters. The FDA’s current emergency import process takes weeks. It needs to be cut to 72 hours.

Climate change isn’t a future threat to drug supplies. It’s happening now. Every storm that hits a manufacturing hub is a warning. And every delay in fixing the system puts lives at risk.

What Patients Can Do

You can’t control the weather. But you can prepare. If you rely on a medication that’s been in short supply-like insulin, IV fluids, or chemotherapy drugs-talk to your doctor about:- Whether there’s a therapeutically equivalent alternative

- If you can get a 30-day emergency supply on hand

- Whether your pharmacy is part of a hospital network with access to backup stock

Don’t wait for a disaster to ask these questions. Ask now. Because when the next storm comes, you won’t have time.

Why do natural disasters cause drug shortages?

Natural disasters like hurricanes and floods damage pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, destroy power grids, and disrupt transportation routes. Many critical drugs are made in just one or two facilities, so when one plant shuts down, there’s no backup. The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain is built for efficiency, not resilience-meaning even one storm can cut off access to life-saving medications like insulin, IV fluids, and chemotherapy drugs.

Which drugs are most at risk during natural disasters?

Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable-especially saline solution, antibiotics, insulin, and chemotherapy drugs. These medications are often made in centralized facilities with no alternatives. For example, 60% of U.S. IV fluids come from one plant in North Carolina. When Hurricane Helene hit in 2024, that single facility went offline, triggering nationwide shortages. Generic drugs are also at higher risk because they have lower profit margins, so manufacturers invest less in backup systems.

How long do drug shortages last after a natural disaster?

Shortages can last from 3 months to over a year, depending on the damage. Hurricanes typically cause 6-18 month disruptions because they destroy infrastructure like power and water systems. Tornadoes cause shorter, 3-9 month shortages focused on specific drugs from a single plant. It takes 6-12 months to restart a damaged facility and 2-3 years to build a new one with FDA-approved equipment. Even after repairs, supply chains take months to recover fully.

Are drug shortages getting worse because of climate change?

Yes. Between 2017 and 2024, climate-related disruptions caused 32% of all U.S. drug shortages. NOAA projects a 25-30% increase in Category 4-5 hurricanes by 2030. Since 65.7% of U.S. pharmaceutical facilities are in counties hit by weather disasters, the risk is rising fast. The 2024 hurricane season was the most damaging on record, with multiple facilities hit in quick succession. Without major changes, climate-related shortages could increase by 150% by 2030.

What can be done to prevent future drug shortages?

Three key actions are needed: First, require manufacturers to maintain 90-day emergency stockpiles of critical drugs in geographically separate locations. Second, mandate full supply chain mapping so hidden dependencies are visible. Third, create an FDA fast-track process to approve alternative suppliers within 72 hours during disasters. The FDA’s 2025 proposed rule is a step forward, but it’s not yet mandatory for all drugs. Public pressure and policy changes are needed to make these measures permanent.

Drug shortages aren’t just a logistical problem-they’re a public health emergency. Climate change isn’t coming. It’s already here. And if we don’t fix the supply chain now, the next storm won’t just knock out the lights. It could knock out your medicine.

10 Comments

Dayanara Villafuerte

January 18, 2026So let me get this straight-we’re still letting life-saving meds be made in hurricane-prone zones like it’s 2010? 😅 Meanwhile, my cousin in Puerto Rico still can’t get her insulin without driving 3 hours. We’re not broken. We’re just lazy. 🤦♀️💉

Praseetha Pn

January 20, 2026Who really controls these drug plants? Hint: It’s not the FDA. Big Pharma bought the entire supply chain decades ago-then moved everything to cheap, disaster-prone areas to maximize profits. Now they want us to panic about shortages? Wake up. This was planned. The storms are just the cover-up. 🌪️💊

Naomi Keyes

January 21, 2026It’s not merely about infrastructure-it’s about regulatory inertia. The FDA’s voluntary guidelines are a joke. There is no legal mandate for geographic diversification, no enforceable buffer stock requirements, no penalties for noncompliance. Moreover, the reliance on single-source suppliers for sterile injectables is not just risky-it’s indefensible from a public health ethics standpoint. The system is not merely fragile; it is actively negligent.

Consider this: if a single power outage in a single facility can cause nationwide delays in chemotherapy, then we are not managing a supply chain-we are gambling with human lives. And the most vulnerable? Rural clinics, Medicaid recipients, elderly patients without advocates. They are not collateral damage-they are the intended outcome of a profit-driven model.

AI forecasting tools like Sensos.io? Praise them, yes-but they are bandages on a severed artery. We need structural reform: mandatory dual sourcing, federal investment in redundant production hubs, and a national emergency drug reserve with real-time tracking. Until then, every storm is a foreseeable tragedy.

And don’t tell me about cost. The cost of a single missed chemotherapy cycle? $12,000 in emergency care. The cost of a newborn in the NICU getting diluted saline? Permanent organ damage. The cost of inaction? Measured in deaths. And we’re still debating whether to fund a 90-day stockpile?

It’s not about being ‘anti-business.’ It’s about refusing to let corporate efficiency override human survival. This isn’t politics. It’s medicine. And medicine, at its core, must be resilient.

Andrew Short

January 22, 2026Oh, so now we’re blaming climate change for Big Pharma’s laziness? How convenient. These companies could’ve diversified 20 years ago. Instead, they outsourced to the cheapest location and called it ‘globalization.’ Now they want taxpayer money to fix their own bad decisions? No. Let them pay for their own backups. Don’t punish the public for corporate greed.

Robert Davis

January 22, 2026I read the whole thing. Twice. And honestly? I’m just… stunned. Not because I didn’t know this was happening-but because no one talks about it. I have a friend on chemo. She had to switch meds last year because saline ran out. She didn’t even know why. No one told her. It’s terrifying how invisible this crisis is.

Pat Dean

January 23, 2026Let’s be real-this is what happens when you let foreigners run your medicine. Puerto Rico? Michigan? North Carolina? We used to make everything here. Now we’re begging Europe to send saline like it’s 1890. Build it here. Tax the corporations. Stop outsourcing national security.

Max Sinclair

January 25, 2026Thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen this play out in real time-especially after Maria and now Helene. The worst part? The patients never know why their meds are delayed. They just think their doctor’s office is incompetent. We need public awareness, not just policy. This deserves a national news cycle.

christian Espinola

January 25, 2026Another liberal panic piece. Hurricanes have always happened. The solution isn’t to rebuild the entire pharma industry-it’s to stop pretending we need so many ‘critical’ drugs in the first place. Maybe if people stopped being so dependent on IV fluids and antibiotics, we wouldn’t be in this mess. Self-reliance, folks.

Stacey Marsengill

January 25, 2026They’ve been warning us for years. Remember the 2017 insulin shortage? The same people who ignored it are now acting shocked. It’s not about storms. It’s about control. Who benefits when people are desperate for medicine? The same ones who own the factories. And guess what? They’re still making billions.

Aysha Siera

January 26, 2026This is why I don’t trust any meds made after 2015.