Corticosteroids are one of the most powerful tools doctors have to calm down an overactive immune system. For people with autoimmune diseases like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or vasculitis, these drugs can mean the difference between constant pain and a manageable life. But they’re not a simple fix. While they work fast-often reducing swelling and fatigue within hours-they come with risks that grow the longer you take them. Understanding both the benefits and the long-term effects is key to using them safely.

How corticosteroids stop inflammation

Corticosteroids, like prednisone and methylprednisolone, mimic cortisol, the body’s natural stress hormone. When your immune system attacks your own tissues-like joints in rheumatoid arthritis or the skin in psoriasis-it releases inflammatory chemicals. Corticosteroids block those signals at the genetic level. They turn down genes that make proteins like tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukins, which drive inflammation. They also shut down phospholipase A2, an enzyme that creates more inflammatory messengers. This isn’t just surface-level relief. It’s a deep reset of the immune response.

That’s why they’re the first-line treatment for flare-ups. If you’re diagnosed with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis or severe vasculitis, you might get high-dose IV methylprednisolone pulses right away. Unlike methotrexate or azathioprine, which can take weeks to kick in, corticosteroids often bring relief in days, sometimes even hours. For someone struggling to walk or breathe because of inflammation, that speed is life-changing.

When corticosteroids work best

They’re not a cure-all, but they’re highly effective for several conditions. In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), they reduce kidney inflammation and prevent organ damage. For inflammatory bowel disease, they help control flare-ups of Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. In asthma, they shrink swollen airways. Even in skin conditions like pemphigus, where blisters form from immune attacks on the skin, corticosteroids can bring the disease under control.

But they don’t work for every autoimmune disease. For advanced type 1 diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, or late-stage primary biliary cholangitis, corticosteroids offer little to no benefit. Why? Because in these cases, the damage is already done-too many cells are destroyed. Early-stage type 1 diabetes, where some insulin-producing cells remain, might still respond. The same goes for early primary biliary cholangitis. It’s not about the disease name-it’s about how much tissue is still alive and salvageable.

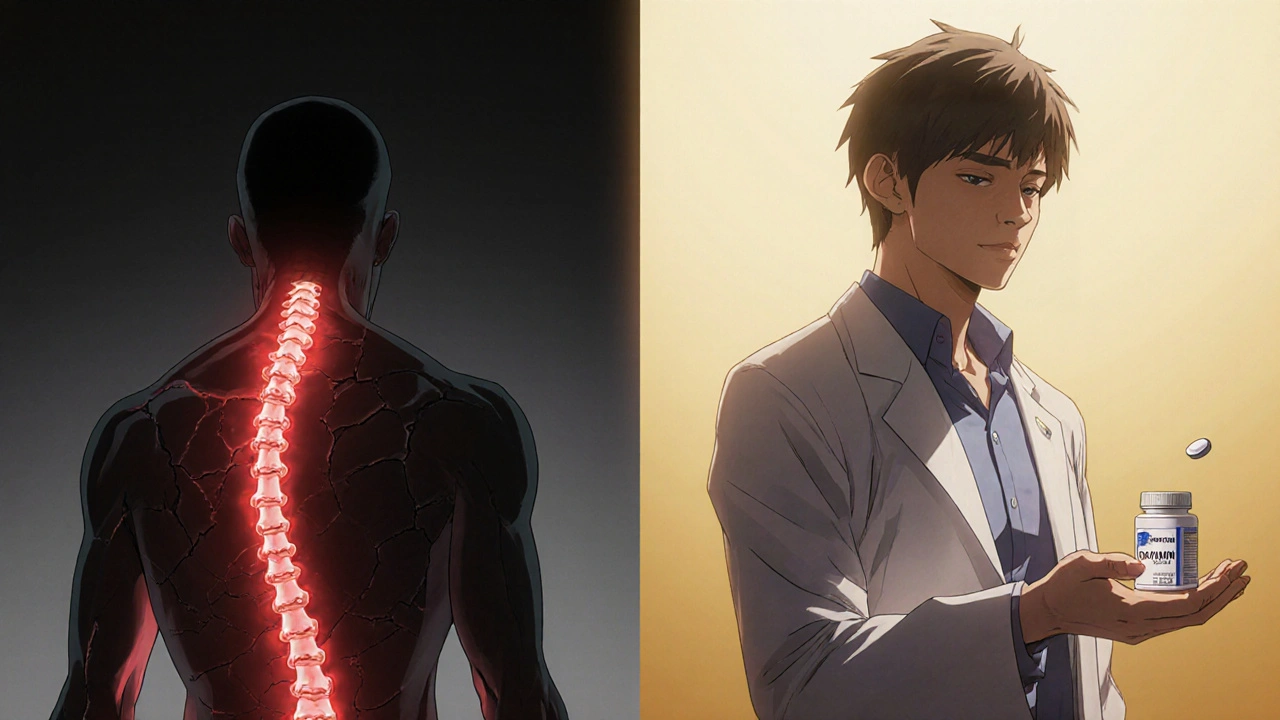

The cost of quick relief: Long-term side effects

The longer you take corticosteroids, the more your body pays for that fast relief. One of the biggest risks is bone loss. Up to 40% of people on long-term steroids develop osteoporosis. That’s why doctors often prescribe calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates alongside steroids. Even low doses over months can weaken bones enough to cause fractures from simple falls.

Cataracts are another common problem. After two years of daily use, the risk jumps significantly. You might not notice blurry vision right away, but over time, clouding of the lens can require surgery. High blood pressure, weight gain, and fluid retention are also typical. Many people gain 10-20 pounds within months, not from eating more, but from how the drug changes how the body stores fat and holds water.

Then there’s adrenal insufficiency. Your body stops making its own cortisol because the drug tells it, “We’ve got this.” If you stop suddenly, your body can’t catch up. That’s dangerous-it can lead to low blood pressure, vomiting, and even shock. That’s why you never quit steroids cold turkey. You taper slowly, often over weeks or months, letting your adrenal glands wake up again.

Other effects include thinning skin, easy bruising, mood swings, trouble sleeping, and higher blood sugar levels. People with diabetes may find their numbers spike. Some notice darker patches on their skin or increased sensitivity to sunlight. Sunscreen isn’t optional-it’s necessary.

How doctors try to minimize the damage

No one wants to be on corticosteroids longer than needed. That’s why the goal isn’t just to control the disease-it’s to use the lowest possible dose for the shortest time. Doctors aim for “targeted remission.” For lupus, that might mean reducing protein in the urine. For rheumatoid arthritis, it’s less joint swelling and normal blood tests. Once the disease is quiet, they start adding other drugs to wean you off steroids.

That’s where combination therapy comes in. Drugs like methotrexate, azathioprine, or rituximab help keep the disease under control so you can lower your steroid dose. One study showed that adding rituximab to prednisone in autoimmune hemolytic anemia doubled the time before relapse compared to steroids alone. That’s a big win. It means fewer side effects and more years without flare-ups.

Topical versions help too. Inhaled steroids for asthma or creams for eczema deliver the drug right where it’s needed, with far less risk to the rest of the body. For people with severe skin conditions, this can cut systemic exposure by 80% or more.

When to consider alternatives

Biologics like rituximab, abatacept, or TNF inhibitors are changing the game. They’re more targeted than steroids-they don’t blanket the whole immune system. That means fewer side effects. But they’re expensive, and not everyone responds. For now, steroids are still the go-to for acute flares because they’re fast, cheap, and widely available. The future isn’t replacing steroids-it’s using them smarter. Short bursts to get control, then switching to a safer long-term option.

Research is also looking at new drugs that mimic the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids without the side effects. One promising target is GILZ, a protein that helps cortisol do its job. If scientists can develop a GILZ-based therapy, it could offer the benefits of steroids without the bone loss or weight gain. But that’s still years away.

What you should ask your doctor

If you’re on corticosteroids, here are five questions to ask:

- What’s my target dose, and how will we know when I can start reducing it?

- What bone-protecting treatments are you recommending? (Calcium, vitamin D, bisphosphonates?)

- Am I at risk for cataracts? When should I get my first eye check?

- What’s the plan if I need to stop this drug? Will I taper slowly?

- Are there other medications I can add to help me get off steroids sooner?

Keep a symptom diary. Note when you feel better, when you feel worse, and any new side effects. That helps your doctor adjust your plan. Don’t skip follow-ups. Blood pressure, blood sugar, and bone density scans aren’t optional-they’re part of staying safe.

Final thoughts: Balance, not fear

Corticosteroids aren’t evil. They’re a tool-powerful, effective, and sometimes essential. For many, they’ve meant getting back to work, playing with grandchildren, or sleeping through the night. But they’re not harmless. The key is using them with awareness. Work with your doctor to get off them as soon as safely possible. Use combination therapies. Monitor your body. Protect your bones. Watch your eyes. And don’t be afraid to ask for alternatives.

The goal isn’t to avoid steroids entirely-it’s to use them as a bridge, not a lifetime sentence. With the right plan, you can control your disease without letting the treatment control your life.

How quickly do corticosteroids work for autoimmune diseases?

Corticosteroids often start working within hours to a few days. Unlike other immunosuppressants like methotrexate, which can take weeks to show results, steroids rapidly suppress inflammation. For example, someone with a lupus flare might feel less joint pain or reduced swelling within 24 to 48 hours after starting prednisone.

Can corticosteroids cure autoimmune diseases?

No, corticosteroids do not cure autoimmune diseases. They suppress the immune system’s overactive response, which reduces symptoms and prevents damage. But once you stop taking them, the disease can return. They’re used to manage the condition, not eliminate it. Long-term control usually requires other medications like methotrexate or biologics.

Are there autoimmune diseases that don’t respond to corticosteroids?

Yes. Corticosteroids are ineffective in advanced stages of type 1 diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, and late-stage primary biliary cholangitis. In these cases, the target tissues (like insulin-producing cells or liver bile ducts) are too damaged for immune suppression to help. Early-stage versions of these diseases may still respond, but only if some functional cells remain.

What’s the biggest risk of long-term corticosteroid use?

The biggest risk is osteoporosis-bone thinning that leads to fractures. Up to 40% of people on long-term steroids develop it. Other major risks include cataracts, adrenal insufficiency, high blood pressure, and weight gain. These side effects are dose- and duration-dependent, which is why doctors aim for the lowest effective dose and shortest possible treatment time.

Can I stop taking corticosteroids if I feel better?

Never stop suddenly. Even if you feel fine, your adrenal glands may have stopped making cortisol. Stopping abruptly can cause adrenal crisis-low blood pressure, nausea, confusion, and even death. Always taper off under medical supervision. Your doctor will slowly reduce your dose over weeks or months to let your body resume natural cortisol production.

Do corticosteroids interact with other medications?

Yes. Corticosteroids can interact with blood thinners, diabetes medications, antifungals, and some antibiotics. They can also reduce the effectiveness of vaccines. Always tell your doctor about every medication, supplement, or herb you’re taking. Some combinations can increase side effects like high blood sugar or bleeding risk.

Is there a safer alternative to oral corticosteroids?

For some conditions, yes. Inhaled steroids are safer for asthma. Topical creams work well for skin conditions like eczema or psoriasis. Injectable steroids can target specific joints without affecting the whole body. For systemic diseases, newer biologics like rituximab or TNF inhibitors offer similar control with fewer long-term side effects, though they’re more expensive and not always covered by insurance.

8 Comments

Tom Shepherd

November 28, 2025Corticosteroids saved my life after my lupus flare last year. I couldn't walk for weeks, then started prednisone and within 36 hours I was sitting up eating real food. Still dealing with the weight gain and insomnia, but I'd take it over being bedridden any day.

shawn monroe

November 28, 2025Let’s be real-steroids are the nuclear option of immunosuppression. They inhibit NF-kB signaling, suppress Th17 differentiation, and downregulate IL-6 and TNF-alpha transcription via glucocorticoid response elements. The downside? HPA axis suppression, gluconeogenesis upregulation, and collagen degradation leading to osteoporosis. Bottom line: use them like a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. Always pair with bisphosphonates and baseline DEXA scans.

marie HUREL

November 30, 2025I’ve been on low-dose prednisone for 4 years now. The bone density loss was scary, but my rheumatologist got me on denosumab and I’ve stabilized. Also, the mood swings were worse than the joint pain at first. Took me months to realize my anxiety wasn’t ‘just stress’-it was the drug. Still, I’m alive and working. That’s worth it.

Lauren Zableckis

December 1, 2025My mom got cataracts from 18 months of steroids for vasculitis. She had surgery last year. Don’t skip the eye exams. Seriously.

Rebecca Price

December 3, 2025It’s heartbreaking how many people think steroids are a cure. They’re not. They’re a bridge-sometimes a very long, shaky one. But we don’t talk enough about the emotional toll. The isolation. The shame of gaining weight when you’re trying to be healthy. The fear of stopping because you know the flare will come back. We need more support systems, not just prescriptions.

Rhiana Grob

December 3, 2025As someone who’s watched a loved one navigate steroid dependence, I want to emphasize that tapering isn’t optional-it’s medical necessity. I’ve seen people quit cold turkey because they ‘felt fine.’ One ended up in the ER with adrenal crisis. Please, if you’re reading this and you’re on steroids: don’t be brave. Be smart. Talk to your doctor. Follow the plan.

Frances Melendez

December 4, 2025People act like steroids are the devil, but they’re just a tool. The real problem is lazy doctors who don’t push combo therapy hard enough. Why are we still letting patients stay on 10mg of prednisone for 5 years? We have biologics. We have clinical guidelines. If your doctor isn’t trying to wean you off steroids within 6 months, find a new one. This isn’t about fear-it’s about accountability.

Sam HardcastleJIV

December 5, 2025One must contemplate the metaphysical implications of exogenous cortisol: it is not merely a pharmacological intervention, but an existential usurpation of the body’s endogenous homeostatic authority. The adrenal glands, once sovereign, are now reduced to silent, atrophied subjects in a regime of chemical tyranny. One must ask: in relieving the inflammation of the body, do we not also extinguish the flame of its autonomy? The irony is profound-the very substance that grants life may, in its prolonged administration, render the self a stranger to itself.