When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing dangerous side effects is critical. SGLT2 inhibitors like canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin have become popular because they don’t just control glucose-they protect your heart and kidneys. But there’s a hidden cost: these drugs significantly raise your risk of yeast infections and serious urinary tract problems. If you’ve been prescribed one of these medications and started noticing itching, burning, or unusual discharge, you’re not alone. And if you’ve had a sudden fever or flank pain after starting the drug, that’s not normal-and it’s not rare.

How SGLT2 Inhibitors Work (and Why They Cause Infections)

SGLT2 inhibitors work by blocking a protein in your kidneys that normally reabsorbs glucose back into your bloodstream. Instead, the sugar gets flushed out through your urine. That’s the whole point-it lowers blood sugar without triggering low blood sugar episodes like insulin or sulfonylureas can. But here’s the catch: sugar in your urine is like a dinner bell for bacteria and fungi.

Your genital area and urinary tract are naturally home to microbes, but when glucose starts leaking into your urine at rates of 40 to 110 grams per day, yeast-especially Candida-thrives. This isn’t a theoretical risk. Clinical trials show that 3% to 5% of people taking SGLT2 inhibitors develop genital yeast infections within the first few months. For women, that usually means vulvovaginal candidiasis: itching, swelling, thick white discharge. For men, it’s balanitis: redness, soreness, and sometimes peeling skin on the penis. These aren’t minor annoyances. They can be painful, recurrent, and disruptive to daily life.

The Bigger Danger: Urinary Tract Infections That Turn Life-Threatening

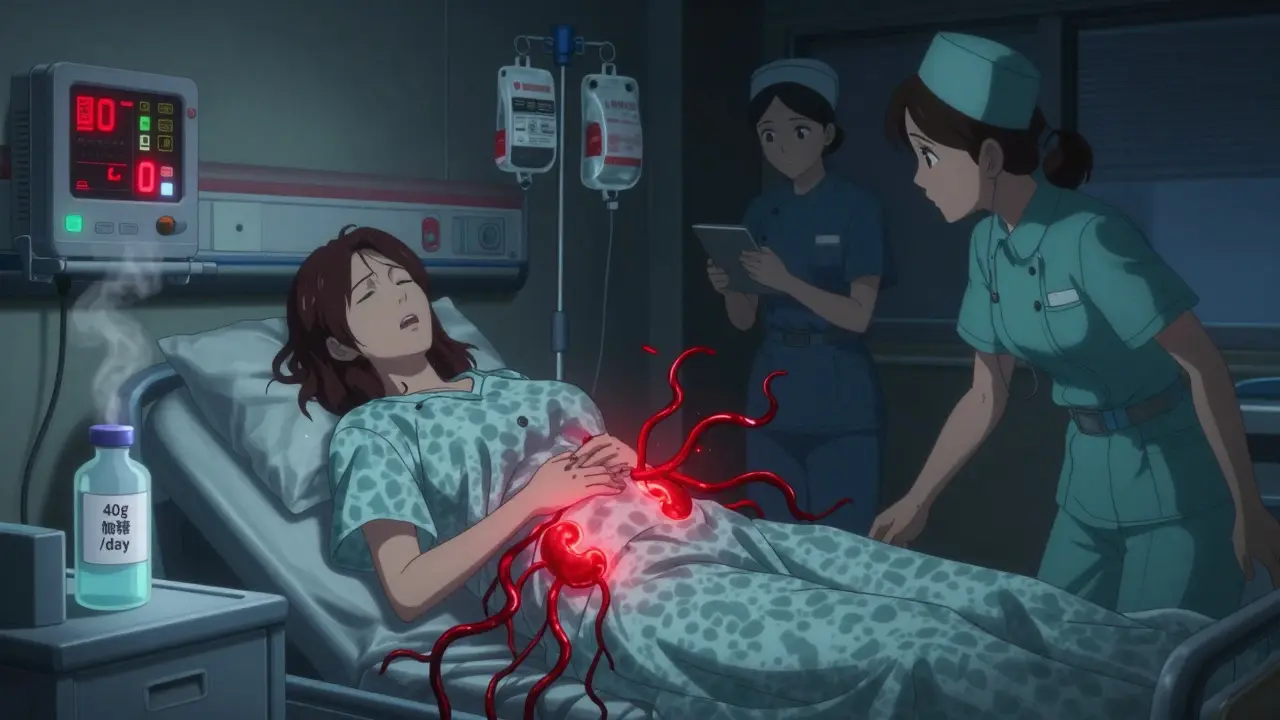

Genital infections are bad enough, but the real concern is what happens when those microbes travel upward. SGLT2 inhibitors increase your risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) by nearly 80% compared to other diabetes drugs like DPP-4 inhibitors or metformin. Most UTIs are mild and treatable with antibiotics. But in some cases, they spiral into something far worse.

The FDA reviewed over 19 cases of urosepsis-bloodstream infections triggered by UTIs-in the first two years after these drugs hit the market. Ten of those patients were on canagliflozin, nine on dapagliflozin. All were hospitalized. Four needed intensive care. Two required dialysis because their kidneys failed. The average time from starting the drug to hospitalization? Just 45 days.

One documented case involved a 64-year-old woman who developed emphysematous pyelonephritis-a rare, gas-forming kidney infection-while taking dapagliflozin. She needed surgery, 14 days of IV antibiotics, and later had a recurrence after restarting the drug. Another patient developed a perinephric abscess. These aren’t outliers. They’re warning signs built into the drug’s mechanism.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on SGLT2 inhibitors gets these infections. But some people are far more vulnerable. Risk factors include:

- Being female (due to shorter urethra and anatomy)

- Age over 65

- History of recurrent UTIs or yeast infections

- Poor genital hygiene

- High HbA1c levels (above 8.5%)

- Chronic kidney disease (eGFR below 60)

- Being immunocompromised

A 2024 study in Diabetes Care created a simple 5-point risk score to identify people with over a 15% chance of developing a serious UTI on these drugs. If you have three or more of these factors, you’re in the high-risk group. For those patients, switching to a GLP-1 receptor agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor might be safer-even if the SGLT2 inhibitor works well for blood sugar control.

Fournier’s Gangrene: A Rare but Deadly Complication

One of the most terrifying complications linked to SGLT2 inhibitors is Fournier’s gangrene-a rare, fast-spreading necrotizing infection of the genitals and perineum. It’s a medical emergency. The infection destroys tissue, can cause septic shock, and has a mortality rate of up to 30% if not treated immediately.

The European Medicines Agency added a warning about this in 2016 after reviewing multiple cases. Patients described sudden, severe pain, swelling, redness, or a foul odor around the genitals. Many had no prior history of infection. Some were on the drug for only a few weeks. The key takeaway? If you feel sudden, intense discomfort in your genital area, especially with fever or feeling generally unwell, don’t wait. Go to the ER. Delaying treatment by even 12 hours can be fatal.

What Should You Do If You’re on an SGLT2 Inhibitor?

If you’re already taking one of these drugs, here’s what you need to do right now:

- Check your genital area daily for redness, swelling, itching, or unusual discharge.

- Drink plenty of water-aim for at least 2 liters a day. This helps flush sugar out faster.

- Practice good hygiene: wipe front to back, wear cotton underwear, avoid tight clothing, and change out of wet swimsuits or workout gear immediately.

- Don’t ignore symptoms. A burning sensation when urinating, frequent urges, or lower back pain aren’t "just a UTI." They could be the start of something serious.

- Call your doctor immediately if you have a fever above 100.4°F, chills, nausea, or feel unusually weak.

Some patients ask if cranberry juice or supplements help. A 2023 FDA safety update noted that cranberry products reduced UTI incidence by 29% in SGLT2 inhibitor users-but this isn’t an official recommendation. It’s a promising observation, not a substitute for medical care.

Are SGLT2 Inhibitors Still Worth It?

Yes-for the right person. If you have heart disease, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease, these drugs can cut your risk of death, hospitalization, and dialysis. The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial showed empagliflozin reduced cardiovascular death by 38%. The CANVAS trial showed canagliflozin lowered heart attack and stroke risk by 14%. That’s powerful.

But if you’re a healthy 50-year-old with well-controlled diabetes and no heart or kidney issues, the infection risk may outweigh the benefit. Many endocrinologists now reserve SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with established cardiovascular or renal disease. For others, GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide or dulaglutide offer similar weight loss and glucose control without the yeast infection risk.

The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for past UTIs before starting SGLT2 inhibitors. If you’ve had three or more in the last year, consider alternatives.

When to Stop or Switch

You shouldn’t stop your medication on your own. But if you’ve had:

- Two or more yeast infections in six months

- A UTI that required hospitalization

- Any signs of Fournier’s gangrene (sudden pain, swelling, fever)

then talk to your doctor about switching. Discontinuation rates are high-nearly 24% of patients stop SGLT2 inhibitors within two years because of side effects, compared to 14% for DPP-4 inhibitors. That’s not because the drugs don’t work. It’s because the side effects are too disruptive-or too dangerous.

Many patients feel guilty for stopping a "heart-protective" drug. But your quality of life matters too. There are other options. And your doctor should be helping you weigh the trade-offs-not just pushing the latest trend.

What’s Next for These Drugs?

Manufacturers are working on solutions. Newer drugs like dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors aim to reduce glucose excretion while still lowering blood sugar. Risk prediction tools are being developed to identify high-risk patients before they start. Some clinics now require patients to sign a consent form outlining infection risks before prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors.

But the bottom line hasn’t changed: these drugs are powerful, but they come with real, documented dangers. Ignoring them isn’t bravery-it’s negligence. Understanding them isn’t fear-it’s responsibility.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors cause yeast infections in men?

Yes. While vulvovaginal candidiasis is more common in women, men taking SGLT2 inhibitors can develop balanitis-an inflammation of the head of the penis. Symptoms include redness, itching, swelling, and sometimes a thick, white discharge. It’s caused by the same yeast (Candida) that thrives in sugary urine. Good hygiene and prompt treatment with antifungal creams usually resolve it, but recurrence is common if the drug continues.

Are SGLT2 inhibitors safe if I’ve had a UTI before?

If you’ve had recurrent urinary tract infections (three or more in the past year), SGLT2 inhibitors are generally not recommended. Studies show your risk of another infection, including severe or complicated ones, increases significantly. Your doctor should consider alternatives like GLP-1 receptor agonists or DPP-4 inhibitors, which don’t increase urinary glucose levels.

How long after starting an SGLT2 inhibitor do infections usually appear?

Most genital infections occur within the first 3 months of starting the drug. Urinary tract infections can appear anytime, but the highest risk is in the first 60 to 90 days. The FDA found the median time to hospitalization for serious infections like urosepsis was 45 days. That’s why early monitoring is critical.

Can drinking more water prevent these infections?

Drinking more water helps-by diluting glucose in the urine and flushing out bacteria faster. But it’s not a guarantee. Studies show that even with high fluid intake, the risk remains elevated compared to other diabetes medications. It’s one part of prevention, not a cure. Hygiene, monitoring, and prompt treatment are just as important.

Should I stop taking my SGLT2 inhibitor if I get a yeast infection?

Don’t stop without talking to your doctor. A single yeast infection can often be treated with antifungal creams or oral medication. But if it comes back, especially more than once, that’s a red flag. Recurrent infections mean the drug is creating an environment your body can’t control. In that case, switching to a different diabetes medication is usually the safest long-term choice.

Final Thoughts

SGLT2 inhibitors are not dangerous drugs. They’re powerful tools that save lives-especially for people with heart failure or kidney disease. But they’re not for everyone. The sugar in your urine isn’t just a side effect-it’s the reason these infections happen. And if you’re prone to them, continuing the drug is like leaving a door open for trouble.

Know your risk. Listen to your body. And don’t be afraid to ask your doctor: "Is this the right drug for me?" The answer might not be what you expect-but it could keep you healthy for years to come.