When a generic drug hits the market, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know for sure? Traditional measures like partial AUC and Cmax used to be enough. Today, they’re often not. For complex drug formulations-like extended-release painkillers or abuse-deterrent opioids-those old metrics can miss critical differences in how the drug is absorbed. That’s where partial AUC comes in. It’s not just another number. It’s a precision tool that looks at drug exposure during the exact time window that matters most for safety and effectiveness.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

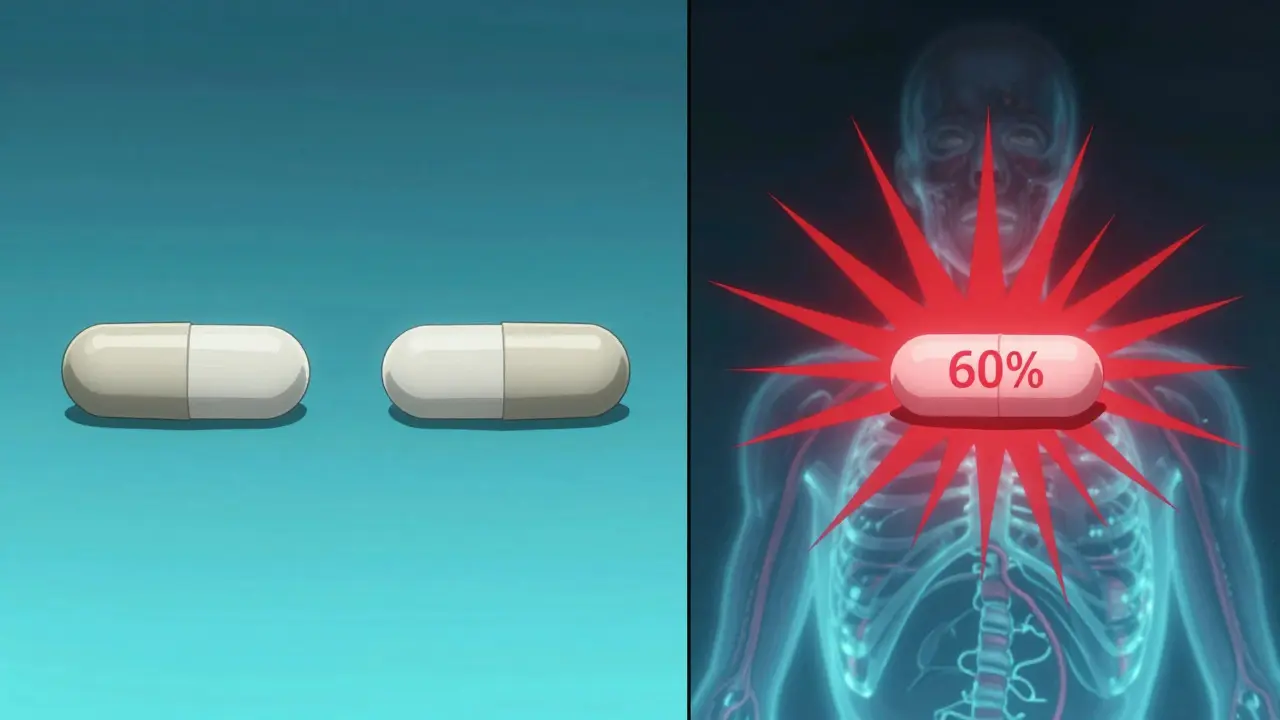

For decades, bioequivalence was judged using two numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and total AUC (the total drug exposure over time). If the generic’s Cmax and AUC fell within 80-125% of the brand’s, it was approved. Simple. Clean. But for drugs that release slowly, or have multiple release phases, this approach breaks down. Take an extended-release oxycodone tablet. The brand product might release 40% of its dose in the first two hours, then trickle out the rest over 12 hours. A generic might hit the same total AUC and similar Cmax-but what if it releases 60% in the first two hours? That’s a problem. Too much early exposure could lead to overdose risk. Too little could mean no pain relief. Total AUC doesn’t catch this. Cmax might not either, if the peak is delayed or flattened. This isn’t theoretical. In 2014, a study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic products that passed traditional bioequivalence tests failed when tested with partial AUC. When researchers added fed-state testing, the failure rate jumped to 40%. That means nearly half the generics that looked fine on paper could have been clinically unsafe.What Is Partial AUC (pAUC)?

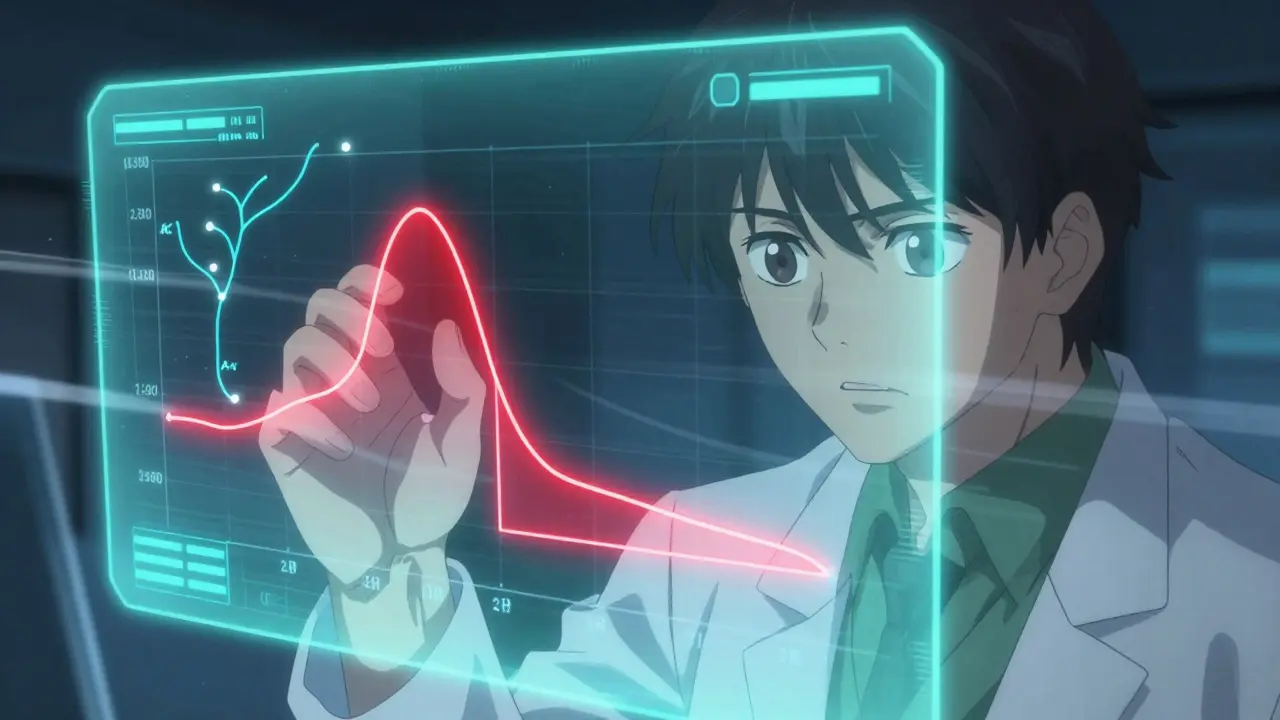

Partial AUC is the area under the drug concentration-time curve-but only for a specific time interval, not the whole curve. Think of it like zooming in on a graph. Instead of looking at the entire 24-hour profile, you focus only on the first 2 hours, or the first 4 hours, or the time when concentrations are above 50% of Cmax. That’s the region where absorption differences matter most. The FDA and EMA began pushing for pAUC after realizing that traditional metrics couldn’t reliably assess products like:- Extended-release opioids

- Abuse-deterrent formulations

- Mixed-release tablets (IR + ER combo)

- Modified-release CNS drugs

How Is pAUC Calculated?

There’s no single way to define the time window. The FDA gives options, and the choice depends on the drug’s behavior:- Time-based: pAUC from 0 to 2 hours, or 0 to 4 hours

- Cmax-based: pAUC from time zero until the concentration drops to 50% of Cmax

- Tmax-based: pAUC from zero to the time when the reference product reaches its peak concentration

- Concentration threshold: pAUC from time zero until concentration falls below a clinically relevant level

Why pAUC Is Changing Generic Drug Development

The rise of pAUC has reshaped how generic drug companies design studies. In 2022, a biostatistician at Teva reported that adding pAUC to an extended-release opioid study increased their sample size from 36 to 50 subjects. That added $350,000 to development costs. But it also caught a 22% difference in early exposure that traditional metrics missed-preventing a potentially dangerous product from reaching patients. On the flip side, companies without deep PK expertise are struggling. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 63% of respondents needed extra statistical help for pAUC analyses-compared to just 22% for traditional methods. Job postings for bioequivalence specialists now list pAUC expertise as a requirement in 87% of cases. And it’s not just about cost. Regulatory rejections are rising. FDA inspection reports from 2022 showed 17 ANDA submissions were rejected solely due to incorrect pAUC time intervals. That’s 8.5% of all bioequivalence-related deficiencies that year.Who Uses pAUC-and Where?

pAUC isn’t used for every generic drug. It’s reserved for the most complex products:- CNS drugs: 68% of new submissions require pAUC

- Pain management: 62%

- Cardiovascular agents: 45%

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite its value, pAUC isn’t perfect. The biggest issue? Inconsistency. Each FDA product-specific guidance (there are over 2,000) can define pAUC differently. Only 42% of them clearly explain how to pick the time interval. That creates confusion. A developer designing a generic for one drug might use a 0-2 hour window. For another, the same regulator might require 0-Tmax. No standardization means longer development cycles. The IQ Consortium reported in 2023 that inconsistent pAUC rules across the U.S., EU, and other regions add 12-18 months to global generic drug approvals. That delays patient access and drives up costs. The FDA is trying to fix this. In January 2023, it launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC cutoff times based on reference product data. Early results look promising. By 2027, Evaluate Pharma predicts 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC-up from 35% in 2022.What This Means for Patients

You might never hear the term “partial AUC.” But it’s working behind the scenes to keep you safe. It’s why your extended-release painkiller doesn’t cause a sudden high. Why your ADHD medication doesn’t wear off too fast. Why your blood pressure med doesn’t drop too sharply. pAUC doesn’t make generics more expensive-it makes them more reliable. It stops products that look similar on paper from being dangerously different in the body. And as more complex drugs enter the generic market, this tool will become even more essential. The science is sound. The regulatory push is real. The data backs it. pAUC isn’t just a technical upgrade. It’s a shift in how we think about bioequivalence-from “same total exposure” to “same exposure when it matters.” And that’s a win for everyone who takes these medicines.What is the main purpose of partial AUC in bioequivalence studies?

Partial AUC measures drug exposure during a specific, clinically relevant time window-like the first 2 hours after dosing-instead of the entire curve. This helps regulators detect differences in how quickly a drug is absorbed, especially for extended-release or abuse-deterrent formulations where total AUC and Cmax might miss dangerous variations in early exposure.

How does partial AUC differ from total AUC?

Total AUC measures the entire drug exposure from dosing until the drug is mostly cleared from the body. Partial AUC zooms in on a short segment-like the absorption phase-where differences in formulation can affect safety and effectiveness. Two drugs can have identical total AUC but very different partial AUC values, meaning one releases drug too fast or too slow at a critical time.

Why do some generic drugs fail bioequivalence testing with pAUC but pass with total AUC?

Because total AUC averages out exposure over time, it can hide early spikes or delays in absorption. A generic might match the brand’s total AUC and Cmax, but if it releases 60% of its dose in the first hour instead of 40%, that’s a risk. Partial AUC catches this by focusing only on that first hour, where the difference matters most.

Is partial AUC required for all generic drugs?

No. It’s only required for complex formulations where traditional metrics are insufficient-like extended-release opioids, abuse-deterrent products, and certain CNS or cardiovascular drugs. As of 2023, over 127 specific products require pAUC in their bioequivalence studies, but most simple immediate-release generics still use only Cmax and total AUC.

What are the biggest challenges in using partial AUC?

The biggest challenges are defining the right time window and dealing with higher variability. Since pAUC focuses on a smaller part of the curve, the data is noisier, often requiring larger study sizes (25-40% bigger than traditional studies). Also, regulatory guidelines vary across products, and only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly explain how to choose the cutoff time, leading to confusion and rejected applications.

14 Comments

Candice Hartley

January 26, 2026So basically pAUC is like checking if your painkiller doesn't hit you like a truck in the first 30 mins? Makes sense.

Conor Flannelly

January 28, 2026It's funny how we used to think 'same total exposure = same effect' like drugs were just buckets of chemicals. But the body isn't a beaker. Timing is everything. That 2-hour window? That's when the brain starts screaming for relief-or when it starts shutting down. pAUC forces us to think like physiology, not just pharmacokinetics. We're finally measuring what matters, not just what's easy to measure. The fact that 40% of generics failed under fed-state pAUC? That's not a regulatory headache. That's a patient safety wake-up call.

Harry Henderson

January 28, 2026THIS. Finally someone gets it. Big Pharma wants you to think generics are all the same. They're not. And if your pain med spikes too fast, you're one bad pill away from an ER trip. Stop letting corporations cut corners on life-saving meds.

Kegan Powell

January 29, 2026Love this breakdown 🙌 It’s wild how we’ve been flying blind for decades with just Cmax and total AUC. pAUC is like switching from a blurry photo to 4K. You can actually see the problem. The fact that the FDA’s now using ML to auto-pick time windows? That’s next-level. I hope this becomes standard for all complex drugs, not just opioids. What about ADHD meds? Or epilepsy drugs? Same damn issue.

John O'Brien

January 30, 2026My cousin took a generic oxycodone and passed out in the grocery store. They said it was 'bioequivalent.' Bullshit. pAUC would’ve caught the spike. This isn’t about cost-it’s about not killing people. Why are we still debating this?

Kirstin Santiago

February 1, 2026It’s not just about safety-it’s about consistency. I’ve been on ER pain meds for years. Some days I feel fine. Other days I’m useless. Turns out, it’s not me. It’s the generic batch. pAUC could finally make this stop. I’m not asking for brand name. I’m asking for reliable.

suhail ahmed

February 2, 2026Man, in India we still get generics that look like they were made in a garage. But hearing this? It gives me hope. If the FDA is serious about pAUC, maybe the rest of the world will catch up. We need this for antibiotics too-some generics release too slow, and then you get resistance. This isn’t just painkillers. It’s the whole damn system.

Conor Murphy

February 4, 2026My dad died from an opioid overdose. The generic he took was approved under old standards. I’ve spent years trying to make sense of it. This post? It’s the first thing that actually explains what went wrong. Not just ‘bad luck.’ It was a failure of measurement. Thank you for making this clear.

Kathy McDaniel

February 5, 2026so like… if my pain med works one day and not the next, it’s not me being weak? it’s the generic? 😳

Murphy Game

February 6, 2026Let me guess-this whole pAUC thing is just a ploy to keep brand-name drugs expensive. Big Pharma’s lobbying for more testing so generics can’t compete. You think the FDA really cares about patients? Or do they just protect profits? Wake up.

Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

February 8, 2026USA is falling behind. Europe’s been doing this since 2013. We’re still arguing over math while people overdose. This is why I hate American healthcare.

April Williams

February 10, 2026So now we’re going to spend $350k more per drug just to avoid a 22% difference in early absorption? Who’s paying for that? You think your insurance premium isn’t going up? This isn’t safety-it’s corporate greed dressed up as science.

Marian Gilan

February 11, 2026They’re lying. pAUC is a scam. The real reason they want this is so they can track you through your blood levels. Next thing you know, your doctor gets a notification if you take too much. They’re building a drug surveillance state. And you’re all just nodding along like sheep. Wake up.

Paul Taylor

February 13, 2026Look I work in clinical trials and let me tell you the truth nobody wants to do pAUC studies. They’re expensive messy and take forever. But the data doesn’t lie. I’ve seen generics pass Cmax and AUC then blow up in phase 3 because patients got sick within the first hour. We’ve been lucky so far. This isn’t bureaucracy. It’s damage control. And honestly we should’ve done this 20 years ago