Medication Safety Checker

What Happened?

Answer these questions to determine if you experienced a medication error or side effect

Answer questions above to see if this was a medication error, side effect, or adverse drug reaction.

Imagine you take your blood pressure pill as directed. A few hours later, you feel dizzy. Is that a side effect-something expected and known-or did you accidentally take the wrong dose? The difference isn’t just semantics. It changes how your doctor responds, how your pharmacy fixes the problem, and whether the same mistake happens again to someone else.

Millions of people experience medication-related problems every year. In the U.S. alone, medication errors and adverse drug reactions cause over 1.3 million injuries and 128,000 deaths annually, according to the FDA. But here’s the thing: most people-including many healthcare workers-can’t tell the difference between a medication error and a side effect. And that confusion costs lives.

What’s a Medication Error?

A medication error is any preventable mistake that happens while a drug is being prescribed, dispensed, or taken. It’s not about the drug itself. It’s about the process.

Think of it like this: you’re driving. You meant to turn left, but you turned right. That’s not because your car is faulty. It’s because you messed up the action. Medication errors work the same way.

Common types include:

- Wrong dose (32.7% of all errors)

- Wrong timing (11.4% of errors)

- Wrong route (like giving a pill orally when it should be injected)

- Wrong patient (giving someone else’s medication)

- Expired or incorrectly prepared drugs

- Using abbreviations like "U" for units (which can be mistaken for "0" or "4") - a known danger flagged by The Joint Commission

These errors happen at every step: a doctor writes "5 mg" but means "50 mg." A pharmacist fills it right, but the nurse gives it to the wrong patient. A patient takes two pills because they misread the label. None of these are the drug’s fault. They’re system failures.

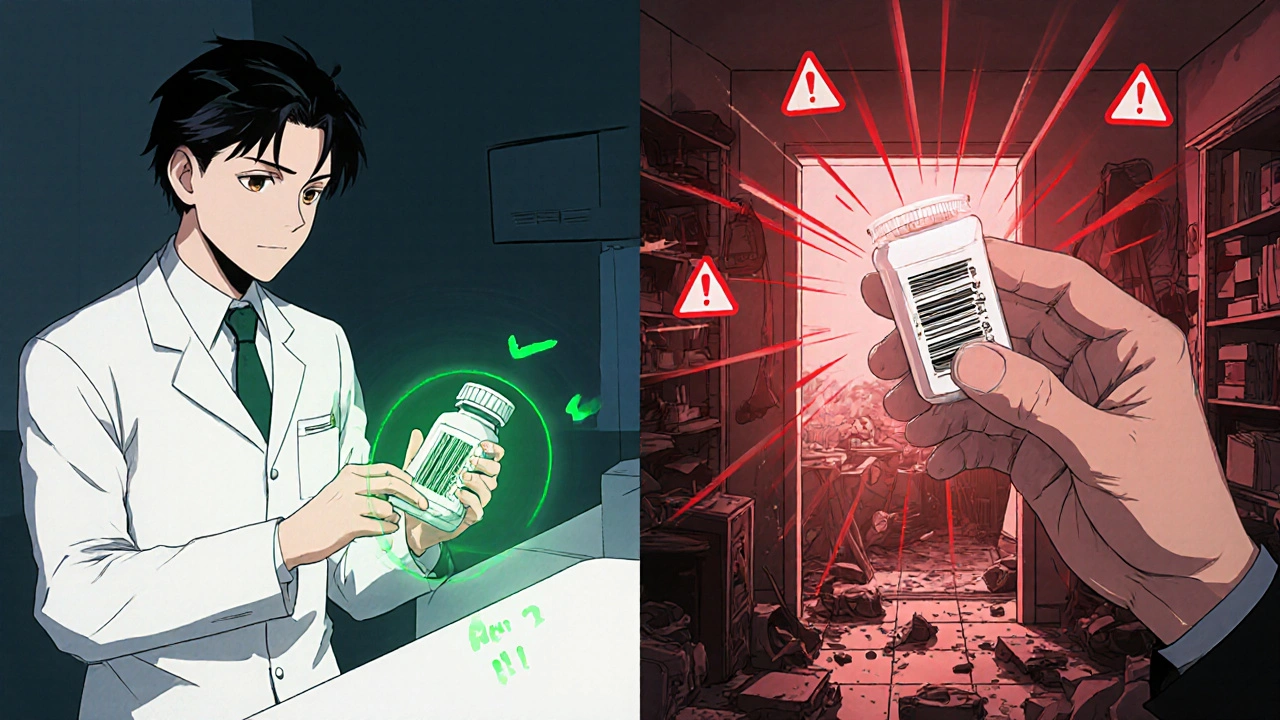

Barcodes on pills, electronic prescriptions, and smart infusion pumps have cut these errors by up to 57% in hospitals that use them. But outside hospitals? In nursing homes and at home? The tools aren’t there. That’s where most errors still happen.

What’s a Drug Side Effect?

A side effect is an expected, known, and predictable reaction to a drug-even when it’s taken perfectly.

It’s not a mistake. It’s a feature of the drug’s biology. Every medication does more than one thing. Sometimes, what it’s supposed to do (like lowering blood pressure) comes with something you didn’t ask for (like dry mouth or drowsiness).

For example:

- Statins (cholesterol drugs) can cause muscle aches

- Antidepressants like SSRIs often cause nausea or sexual dysfunction

- Minoxidil (for hair loss) can cause unwanted facial hair growth

These aren’t accidents. They’re documented. They’re listed in the drug’s package insert. The FDA requires manufacturers to report them. If a drug causes dizziness in 15% of users, that’s a side effect-even if 15% of people feel it.

Here’s the twist: sometimes, side effects are useful. Minoxidil was originally a blood pressure pill. Doctors noticed patients grew more hair. Now it’s a top treatment for baldness. That’s not an error. That’s repurposing a known side effect.

What’s an Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR)?

ADR is the umbrella term for any harmful, unintended reaction to a drug taken correctly. Side effects are a subset of ADRs.

But not all ADRs are side effects. There are two main types:

- Type A (Augmented): Predictable, dose-related. These make up 80% of ADRs. Think: too much blood thinner = bleeding. Too much insulin = low blood sugar.

- Type B (Bizarre): Unpredictable, not dose-related. These are rare (15% of ADRs) but dangerous. Think: allergic reactions, liver failure from a drug you’ve taken for years with no problem.

Side effects are usually Type A. They’re known. They’re common. ADRs include both Type A and Type B. So if you get a rash from a drug you’ve never reacted to before-that’s an ADR, but not a side effect.

Here’s the key: ADRs happen even when the medication is given correctly. No mistake. No misreading. Just the drug doing something harmful that wasn’t the goal.

How to Tell Them Apart: A Simple 5-Step Check

When something goes wrong after taking a drug, ask yourself these questions:

- Did the harm happen? If no harm occurred, it’s a near-miss or potential error-not a side effect or ADR.

- Was the drug taken exactly as prescribed? If yes → it’s an ADR. If no → it’s a medication error.

- Is this reaction listed in the drug’s official information? If yes → it’s a side effect (a type of ADR). If no → it’s a rare ADR.

- Is the reaction dose-dependent? If it gets worse with higher doses → likely Type A ADR or side effect.

- Is this something that only happened to you? If it’s rare, sudden, and unrelated to dose (like a rash, swelling, or breathing trouble) → it’s likely a Type B ADR.

Example: You take lisinopril (a blood pressure pill) and develop a dry cough. That’s a side effect. It’s known. It’s common. It’s not your fault.

But if you took the wrong dose-say, 40 mg instead of 10 mg-and your blood pressure dropped dangerously low? That’s a medication error.

Now, if you took the right dose, and your liver suddenly failed? That’s a Type B ADR. No mistake. No warning. Just bad luck with your biology.

Why This Distinction Matters

Confusing these terms leads to real-world harm.

If you call a medication error a "side effect," you’re saying it’s unavoidable. It’s not. Errors can be fixed with better systems: clearer labels, barcode scanning, electronic prescriptions, pharmacist reviews.

But ADRs? You can’t prevent them all. You can only monitor for them. That’s why hospitals track ADRs with systems like FAERS (FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System). They need to know if a drug is suddenly causing more liver damage than expected.

Healthcare workers often mislabel errors as side effects to avoid blame. A 2022 survey found 42.7% of nurses admitted to doing this. But hiding errors doesn’t protect patients. It prevents fixes.

Patients, too, get confused. A 2022 survey found 78.6% couldn’t tell the difference. So they don’t report problems. Or they blame themselves. "I must be sensitive to this drug," they think-when it was actually the pharmacist who misread the handwriting on the prescription.

Doctors and pharmacists aren’t immune. A 2023 study found only 63.2% of providers could correctly classify a scenario as an error or ADR. Nurses scored lower than doctors. Pharmacists scored the lowest.

That’s not because they’re careless. It’s because the system doesn’t train them clearly. And the tools they use-like electronic health records-often don’t make the distinction easy.

What You Can Do as a Patient

You don’t need to be a doctor to spot the difference. Here’s how to protect yourself:

- Know your meds. Keep a list: name, dose, reason, time taken. Use a pill organizer or app.

- Ask: "Is this a side effect or could this be a mistake?" If you’re unsure, call your pharmacist. They’re trained to answer this.

- Report anything unusual. Even if you think it’s "just a side effect." If it’s new, severe, or unexpected, it might be a rare ADR.

- Check labels. Is the dose written clearly? Is the name correct? Are there typos?

- Don’t assume. If your doctor says, "This side effect is normal," ask: "Is this listed in the official info?" If they can’t point to it, dig deeper.

And if you think you’ve had a medication error? Report it. Not to blame anyone. To help prevent it from happening to someone else.

The Bigger Picture

Technology is helping. Hospitals using barcode systems cut administration errors by nearly 60%. AI tools are now being trained to read doctor’s notes and flag possible errors or unusual ADR patterns.

But the real fix isn’t tech. It’s culture. It’s stopping the habit of calling errors "side effects." It’s training every nurse, pharmacist, and doctor to say: "This wasn’t the drug’s fault. This was our system’s fault. Let’s fix it."

Medication safety isn’t about being perfect. It’s about admitting when we’re not-and changing before someone gets hurt.

13 Comments

Karla Luis

November 24, 2025So basically if your doctor scribbles '5mg' and you take 50mg because you thought it was 50? That's not your fault it's the system's fault. Got it. I'll just blame the pen next time I accidentally swallow my roommate's thyroid med

jon sanctus

November 26, 2025Oh wow. Another ‘let’s overcomplicate medicine’ essay. You know what’s really dangerous? When people like you turn every simple thing into a 2000-word lecture. I take my pills. I don’t care if it’s a Type B ADR or a typo on a barcode. I just want to live. Why do you need to label everything like a lab rat in a PhD thesis?

Kenneth Narvaez

November 26, 2025Incorrect classification of adverse drug reactions leads to confounding in pharmacovigilance datasets. The FDA’s FAERS system suffers from misclassification bias due to layperson misinterpretation of pharmacodynamic vs. iatrogenic causality. The 57% reduction in hospital errors via barcode systems is statistically significant (p < 0.001) but not generalizable to outpatient settings due to lack of interoperable EHR integration. Also, ‘U’ for units is still used in 19% of handwritten scripts per JCAHO 2021 audit.

Christian Mutti

November 27, 2025THIS. IS. A. TRAGEDY. 🥺

Imagine-just imagine-someone’s grandmother dying because a nurse misread a prescription… and then someone says ‘oh it’s just a side effect’… and no one fixes it…

And the system just… keeps… going…

It’s not just medical-it’s moral. It’s spiritual. It’s the death of compassion in a world that’s lost its way. 😭

Sharmita Datta

November 28, 2025They dont want you to know this but pharmaceutical companies profit more from side effects than cures... the cough from lisinopril? That's why they sell cough syrup... the fatigue from statins? That's why they sell energy drinks... the hair loss from chemo? That's why they sell wigs... it's all connected... the system is designed to keep you dependent... you think this is about safety? No... it's about control... they dont want you to understand the difference because then you'd ask why the same drug is sold in 3 different countries with 3 different warning labels...

mona gabriel

November 29, 2025My grandma took her blood pressure pill wrong once. Thought it was the meds. Turned out the pharmacy gave her someone else’s bottle. She didn’t say anything. Thought she was just getting old. Took three weeks before her daughter found the mix-up. No one got punished. No one even apologized. Just… moved on.

That’s the real problem. Not the labels. Not the jargon. The silence.

We’re all just trying not to die. And no one’s listening.

Phillip Gerringer

November 29, 2025Anyone who can’t tell the difference between a medication error and a side effect shouldn’t be allowed to manage their own meds. You don’t get to drive a car without a license. Why are we letting people self-administer life-altering drugs without basic literacy? This isn’t a system failure-it’s a personal responsibility failure. Stop blaming the pharmacist. Learn your pills. Or don’t take them.

jeff melvin

November 30, 2025Side effects are just the cost of doing business. If you can't handle a little dizziness from your antidepressant you're weak. The system isn't broken. You're just not tough enough. People used to take penicillin without knowing what it did. They didn't have apps or pill organizers. They just took it and lived. Maybe you should try that.

Matt Webster

November 30, 2025I work in a nursing home. We see this every day. Elderly folks take meds they don’t understand. Families assume the pharmacy got it right. Nurses are stretched thin. But here’s the thing-we’re not monsters. We want to get it right. We just need better tools, more time, and someone to actually listen when we say, ‘This doesn’t look right.’

It’s not about blame. It’s about support. We’re all just trying to keep people safe.

Stephen Wark

December 2, 2025Oh look, another ‘let’s make medicine more complicated’ post. Meanwhile, real people are dying because they can’t afford their meds, and you’re over here debating whether a cough is a side effect or a system failure. Do you even know what poverty looks like? Or do you just like typing in all caps and pretending you’re a doctor?

Daniel McKnight

December 4, 2025There’s poetry in how we treat our bodies. We swallow chemicals like prayers and hope they’ll fix us without asking why. We call dizziness a side effect when it’s really a scream from a system that forgot to listen.

Maybe the real medicine isn’t in the pill. Maybe it’s in the courage to say: ‘This doesn’t feel right.’

And then being heard.

Jaylen Baker

December 4, 2025THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING I’VE READ ALL YEAR!!! 🙌🙌🙌

My sister had a Type B ADR from a generic antibiotic and the hospital didn’t even document it properly because they called it a ‘side effect’! I spent 3 months fighting to get it corrected in her chart. Now she’s fine. But what about the next person? We need mandatory training. We need public awareness. We need CHANGE. I’m starting a petition. Join me? 💪💊

Fiona Hoxhaj

December 6, 2025One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of pharmacological classification. The binary dichotomy between ‘error’ and ‘side effect’ is a linguistic construct imposed by a capitalist-medical-industrial complex that seeks to absolve itself of accountability by reifying causality through semiotic obfuscation. The very lexicon of ‘Type A’ and ‘Type B’ ADRs is a performative gesture of pseudo-scientific legitimacy, masking the ontological instability of pharmaceutical agency. One wonders-when the label reads ‘may cause dizziness,’ is it not already an admission of inherent harm? And if so, can we truly speak of ‘correct’ administration when the substance itself is inherently violative of homeostasis?