Understanding the Hormonal Connection

As a blogger, I have always been fascinated by the intricate workings of the human body, especially when it comes to hormones. In this article, I will discuss the role of hormones in tumor growth and how they might contribute to the development of cancer. Hormones are chemical messengers that regulate many of our bodily functions, including growth and metabolism. It's important to understand their role in tumor growth, as this knowledge can lead to improved cancer treatments and prevention strategies.

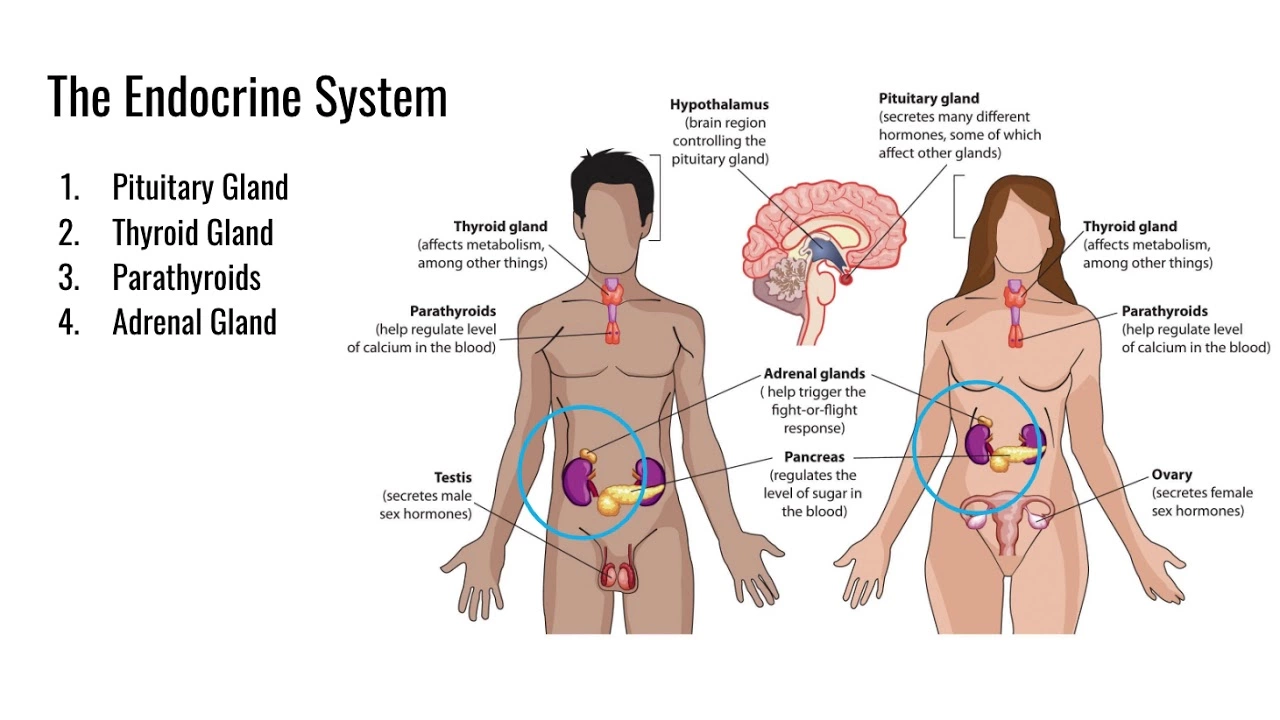

The Endocrine System: A Brief Overview

The endocrine system is a complex network of glands that produce hormones, which are then secreted into the bloodstream. These hormones act as chemical messengers, allowing the body to communicate with itself and maintain homeostasis. Some of the primary glands involved in the endocrine system include the pituitary, thyroid, adrenal, and gonads (testes and ovaries). Hormones produced by these glands regulate a wide range of processes, including growth, development, metabolism, and immune function.

How Hormones Can Influence Tumor Growth

Many hormones have been shown to play a role in the growth of tumors. For example, estrogen, a female sex hormone, has been linked to the development of breast cancer. Similarly, the male sex hormone testosterone has been implicated in the growth of prostate cancer. Other hormones, such as insulin and insulin-like growth factors, have also been connected to the development of various types of cancer. These hormones can promote tumor growth by binding to specific receptors on the surface of cancer cells and triggering a cascade of signaling events that ultimately lead to cell proliferation and tumor growth.

Estrogen and Breast Cancer

Estrogen is a well-known hormone that plays a significant role in the development of breast cancer. It is produced by the ovaries and is responsible for the development and maintenance of female secondary sexual characteristics. Estrogen has been shown to promote the growth of breast cancer cells by binding to estrogen receptors on the surface of the cells, thereby stimulating cell division and tumor growth. This is one of the reasons why hormone therapy, which involves blocking the production or action of estrogen, is often used as a treatment for breast cancer.

Testosterone and Prostate Cancer

Testosterone, the primary male sex hormone, has been linked to the development of prostate cancer. It is produced by the testes and is responsible for the development and maintenance of male secondary sexual characteristics. Testosterone has been shown to promote the growth of prostate cancer cells by binding to androgen receptors on the surface of the cells, thereby stimulating cell division and tumor growth. Hormone therapy, which involves blocking the production or action of testosterone, is often used as a treatment for prostate cancer.

Insulin and Insulin-Like Growth Factors

Insulin and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) are hormones that regulate glucose metabolism and promote cell growth and survival. They have been implicated in the development of several types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer. Insulin and IGFs can promote tumor growth by binding to specific receptors on the surface of cancer cells and triggering a cascade of signaling events that ultimately lead to cell proliferation and tumor growth. Targeting the insulin/IGF signaling pathway is an area of active research in cancer therapy.

The Role of Hormones in Cancer Prevention and Treatment

Understanding the role of hormones in tumor growth has led to the development of several cancer prevention and treatment strategies. For example, hormone therapy, which involves blocking the production or action of specific hormones, is often used as a treatment for hormone-dependent cancers, such as breast and prostate cancer. Additionally, lifestyle factors that can influence hormone levels, such as maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and eating a balanced diet, may help reduce the risk of developing hormone-related cancers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hormones play a significant role in the growth of tumors and the development of cancer. Understanding their role in tumor growth has led to improved cancer treatments and prevention strategies. As a blogger, I hope that this article has provided you with valuable insight into the complex relationship between hormones and cancer. By raising awareness about this important topic, we can all work together to reduce the burden of cancer on our society.

7 Comments

Elle Trent

May 16, 2023While the overview is commendably thorough, the piece skirts around the mechanistic nuance of hormone‑driven oncogenesis, glossing over receptor isoform specificity and downstream PI3K/AKT cross‑talk-classic oversimplifications that seasoned endocrinologists will find glaringly superficial.

Jessica Gentle

May 16, 2023Great summary! To add a practical angle, clinicians often monitor serum estradiol and PSA levels as surrogate markers for therapy response, and emerging data suggest that combining aromatase inhibitors with CDK4/6 blockers can synergistically curb estrogen‑driven proliferation. Also, lifestyle interventions like resistance training have been shown to modulate IGF‑1 pathways, which might complement pharmacologic strategies.

Samson Tobias

May 16, 2023Thank you for tackling such a complex topic. It’s important to remember that behind each hormone‑cancer axis lies a patient narrative, and empowering individuals with knowledge about how diet, sleep, and stress impact hormonal balance can be a catalyst for proactive health management. By integrating regular aerobic exercise, maintaining glycemic control, and fostering psychosocial support, we can collectively attenuate the hormonal milieu that fuels tumor growth.

Alan Larkin

May 16, 2023Actually, the article missed a crucial point: glucocorticoid receptor polymorphisms can modulate tumor microenvironment immunosuppression. If you look at the recent *Nature* paper (2022), they demonstrated that selective GR antagonism re‑sensitizes melanoma to checkpoint inhibitors 😊. So, hormones aren’t just growth signals; they’re also immune regulators.

John Chapman

May 16, 2023One must concede that the author's exposition, albeit laudable in breadth, suffers from a paucity of quantitative rigor. A mere qualitative discussion, devoid of kinetic parameters or dose–response curves, relegates the narrative to the realm of popular science rather than a substantive contribution to oncologic endocrinology.

Tiarna Mitchell-Heath

May 16, 2023Stop spouting recycled textbook fluff; this is 2023, get your facts straight.

Katie Jenkins

May 16, 2023Firstly, let me point out that the term “hormone therapy” is used ambiguously throughout the article; it should be specified whether we refer to agonist, antagonist, or aromatase inhibition modalities. Secondly, the discussion on insulin and IGF‑1 neglects the differential signaling cascades mediated by the insulin receptor isoforms A and B, which have distinct proliferative outcomes. Moreover, the author fails to acknowledge that hyperinsulinemia can lead to decreased levels of sex hormone‑binding globulin, thereby elevating free estrogen-a nuance that is critical for understanding breast cancer risk. Additionally, the piece overlooks the impact of adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin on tumor angiogenesis; recent studies have demonstrated that leptin can activate STAT3 pathways in a hormone‑dependent manner. It is also worth noting that the paper does not differentiate between endocrine‑dependent and endocrine‑responsive tumor subtypes, a distinction that has therapeutic implications. The omission of quantitative data-such as Ki‑67 proliferation indices in hormone‑treated cohorts-makes the argument feel anecdotal. Furthermore, the author’s claim that lifestyle modifications “may help reduce risk” should be buttressed by epidemiological statistics, for example, a 20% risk reduction observed in the Nurses’ Health Study with sustained physical activity. In the realm of prostate cancer, the article glosses over the role of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) versus testosterone, ignoring that DHT possesses a higher affinity for androgen receptors and thus a more potent proliferative effect. On a methodological note, the author should have clarified whether the cited studies employed longitudinal or cross‑sectional designs, as this influences causal inference. Lastly, while the conclusion is optimistic, it would benefit from a more cautious tone, acknowledging the heterogeneity of hormone‑driven cancers and the ongoing need for personalized medicine approaches. In sum, the article provides a solid foundation but requires greater precision, more comprehensive citation, and a nuanced appreciation of hormonal signaling complexity to truly serve its intended audience.